in conversation with Orian Barki

CURA. 43

Coming of Age

Meriem Bennani: This is actually a cool opportunity to have this conversation. We have been working together for years now—the past two years and a half specifically on the animated project For Aicha—and it’s always been such a race against time, a sort of marathon. Although we ask questions to each other every five minutes while we’re working, we don’t ever have time to slow down and discuss bigger philosophical questions about our experiences. I have always made animation mixed with documentary. You started working with animation when we made 2 Lizards in 2020, with a very casual and spontaneous approach, always in dialogue with documentary. While I don’t consider myself a documentary filmmaker, having a more amateur approach to this genre, I think of you as being more grounded in that tradition. Why do you think people make documentaries?

Orian Barki: Documentaries started as anthropological movies. The first documentary ever made (I remember this from film school) was Nanook of the North, a 1922 silent movie that follows the struggles of an Inuit man and his family in the Canadian Arctic. The filmmaker, Robert J. Flaherty, used a type of film that was very inflammable and all of his footage got burnt!

MB: So he never made it?

OB: No, I think he remade it. I don’t remember the full story. The first time, he had developed it and he had started editing, the film was even almost finished. And then it was just burnt in flames.

MB: Don’t joke, because this could happen to us too. We’re not done yet!

OB: No, it won’t happen, it’s all backed up on a cloud. Anyway, that’s how people started making documentaries: through an anthropological lens. I think that documentary storytelling is what is special about human beings. It’s all about storytelling, you know. That’s how we built societies and everything that we have is defined by this act. Telling the story of how something happened, in any art form. When people watch a documentary versus a fiction, there’s something about following a true story that actually happened that is interesting. It gives you this grounding aspect, it adds this special power to it. I think some people lean towards this type of storytelling because life is a really interesting material to work with. It gives you a legitimacy.

MB: And why did YOU start making documentaries? I know you naturally went into that as a teenager. We’re both millennials, we were teens before social media but you already had a practice of filming everything in your teenage years, which is amazing. I wish I had all that footage of myself as a teen… or maybe not! Do you remember why you specifically chose to do that? And why do you think we care so much that something actually happened?

OB: OK, the first question about my own choice is easier to answer. I actually started documentary from filming my own life. I didn’t have this explorer urge of the documentarian going into other people’s lives, I had more of a diaristic urge. I think that I did it because I was interested in remembering things that happened to me and I thought that the camera would help me look at my own life from the outside. It helped me to make sense of things, telling them to myself.

MB: My understanding of you as a teenager is similar to mine. I feel we both have a pretty observational stance. This also has to do with gender and sexuality. I feel we’ve looked at everyone else being teens: girls being so much in their gender, hot girls putting on makeup and ‘boys being boys’ and so on. While I think being queer and not so fem put us both in the place where we felt we didn’t fully experience teenage, coming of age, but rather we observed other people becoming teens, feeling a bit different maybe. If you don’t know how to do makeup it’s easier to film hot fem girls doing that. Maybe that’s why we make documentaries. I don’t want to answer for you, but I think it makes sense that we make films together. We have that gaze on things.

OB: Yeah. And I really like stories too. To reply to your other question of why we care that something actually happened, I really love stories. I grew up watching so much TV and I have always appreciated a good story. I don’t know why for me something that actually happened is more interesting. On a superficial level, it’s even like gossip. Documentary is closer to gossip… When something happens, even if it’s not filmed, I’m excited to have experienced it, but I just cannot fucking wait to tell someone about it! You know? That’s my biggest pleasure. My favorite part of experiencing something is to tell about it after.

MB: That’s also the biggest difference between us and our taste in what we like to watch… I don’t care that something happened. I am often bored by things that look very real. When it’s a Netflix identity show that is so close to my life, I find that so boring. It’s hard for me to watch, I lose interest so fast. While I do love fiction. I love things that could never happen. I like things to be dressed in a way that feels like there is a creative effort, that is exciting for me. I think that this difference of taste and inclinations we have is really interesting because what we’re making together is dressed in a very specific medium that is completely about creating worlds. It’s full world-building. It’s animals. Everything is made from scratch and looks a certain way that only exists in that world. But then their stories are something that happened for real. Or at least it’s made in a way that makes you feel that it happened. It’s so real. It’s very accessible. And I think you’re really good at telling stories, while I’m the worst at gossiping.

OB: You are actually good at it!

MB: Really? Thank you. I think that whenever someone else is sharing a crazy story, everyone reacts like “What? No way. Unbelievable! She didn’t say that!” And then it’s my turn, I have a story too and I swear it was crazy for real, but I just don’t know how to deliver it and get the same reaction. But thank you, I am glad you think I have a gossip potential. I could ask you other questions, but do you have any questions for me?

OB: Well, my question is not as profound as yours. I would like to ask what’s your favorite part of the movie.

MB: OK, I know which one it is. It’s the scene with the character called Yamna, who’s the aunt of the protagonist, Bouchra. Bouchra is visiting home, she lives in New York and she comes back to Morocco. She goes on a car ride with her aunt and while they are catching up, Yamna tells her that she’s not feeling very extroverted and that she feels people are not necessarily drawn to her. She is a middle-aged single woman, which is a demographic that is not often documented. She talks about how she would like to find love and she says she only wants it if it’s going to be easy, with someone she is going to feel good with. At this point, she is not desperate for it anymore. She just doesn’t have patience for being with someone who is going to be dramatic. This is my favorite moment, first because it’s actually a sound bite from me and my aunt in her car, where she very casually opened up in a way that I felt was very deep. There’s a kind of kinship, a depth of natural connection between Bouchra and Yamna. One is a lesbian and the other one is not married, they both are always a bit at the margin. They’re always third wheels, like a +1 in family situations where couples and their kids are seen as a cell. When you’re a floating atom instead, they just assume that you’re available for things. That’s who’s going to take care of the grandmother, that’s who doesn’t need their own hotel room, that’s who kids like to talk to, maybe because they can’t place you or because you don’t have a partner, so you’re not fully an adult. I think there’s this connection, this understanding between them—even though the aunt doesn’t necessarily know that her niece is queer, she understands some kind of kinship between them. That’s my favorite scene.

OB: Tell me about making a personal film. You always made films with your family, but you were never the main character of anything you made.

MB: Yeah, I think on a purely creative level it’s really good and really hard at the same time. What’s really good is that you really care. In general, my compass for a project is if I really care about it. It doesn’t have to be personal, I can care about a million other things that are external to me, but if something ties me emotionally up to that thing, here you go, that’s a given. On the creative level, though, it’s pretty dizzying because of the stance we were talking about, of taking a step back to look at things and having a necessary distance to build a story out of real life, to transform reality into fiction, to transform people into characters…, all these necessary steps that happen in documentary and fiction for me are often impossible. Now, the more the film is coming together and I see it as animated vignettes, the more I’m able to separate myself from it. To accept that I don’t have to like Bouchra, she doesn’t have to be likable because she is not me. I am separating myself from her. And actually she’s pretty annoying many times… The point is that there are moments where I think I would have some kind of judgment, which is fine but it is really hard because you have this weird dysmorphia, where you look at yourself in the mirror, but you can’t judge. You can’t see yourself for how you look because you’re only seeing yourself through subjectivity, and I think that’s what’s happening with the film. Sometimes there are scenes that I wasn’t able to know if they were going to be interesting or not because they are inspired by things that are very personal. It was only possible because we were collaborating. I deferred to you in those moments.

OB: Wait. When do you think she’s being annoying? I am being protective of her.

MB: I think she is an adult, but she regresses a lot when she talks to her mum and she needs this validation. She is pushing her mum to participate in giving her stuff for this film that she is doing really for herself. In those moments she is a bit selfish and self-centered, which may be necessary to write an autobiographical thing because you’re in that space. But I feel like it’s the last thing before she’s resolved and can be fully a responsible adult, responsible for her feelings. What about you?What’s your favorite scene in the film?

OB: My favorite scene in the film is always the latest that we worked on. I like new scenes.

MB: Mmm, do you have another question?

OB: Yeah: how many lesbians does it take to switch a light bulb?

MB: I think I know this answer because I’ve known you for so long. I know your jokes, but I’ll let you answer.

OB: Two: one switches the light bulb, and the other makes a documentary about it.

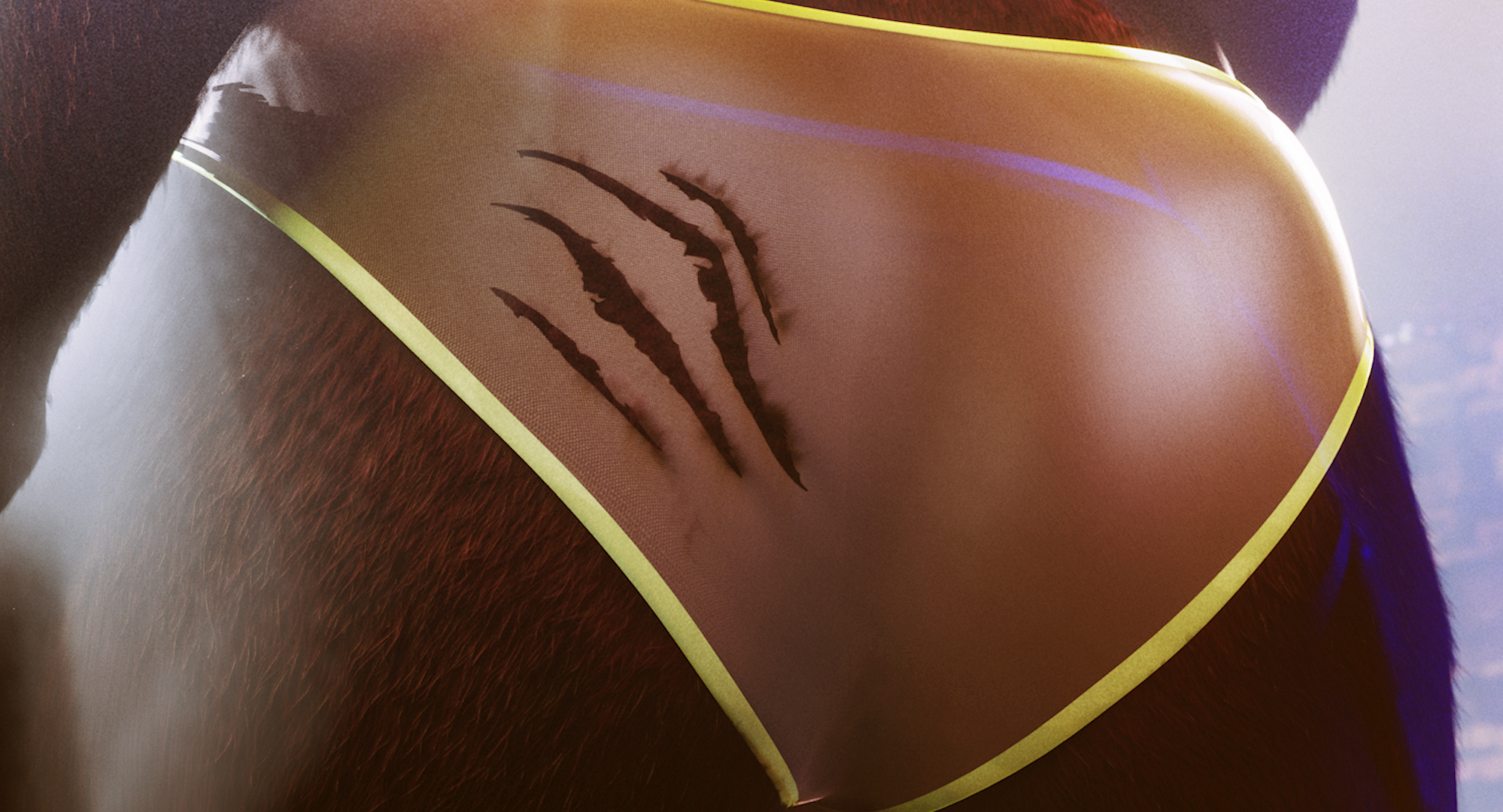

Research for Sole crushing, 2024

Courtesy: the artist and Fondazione Prada, Milan

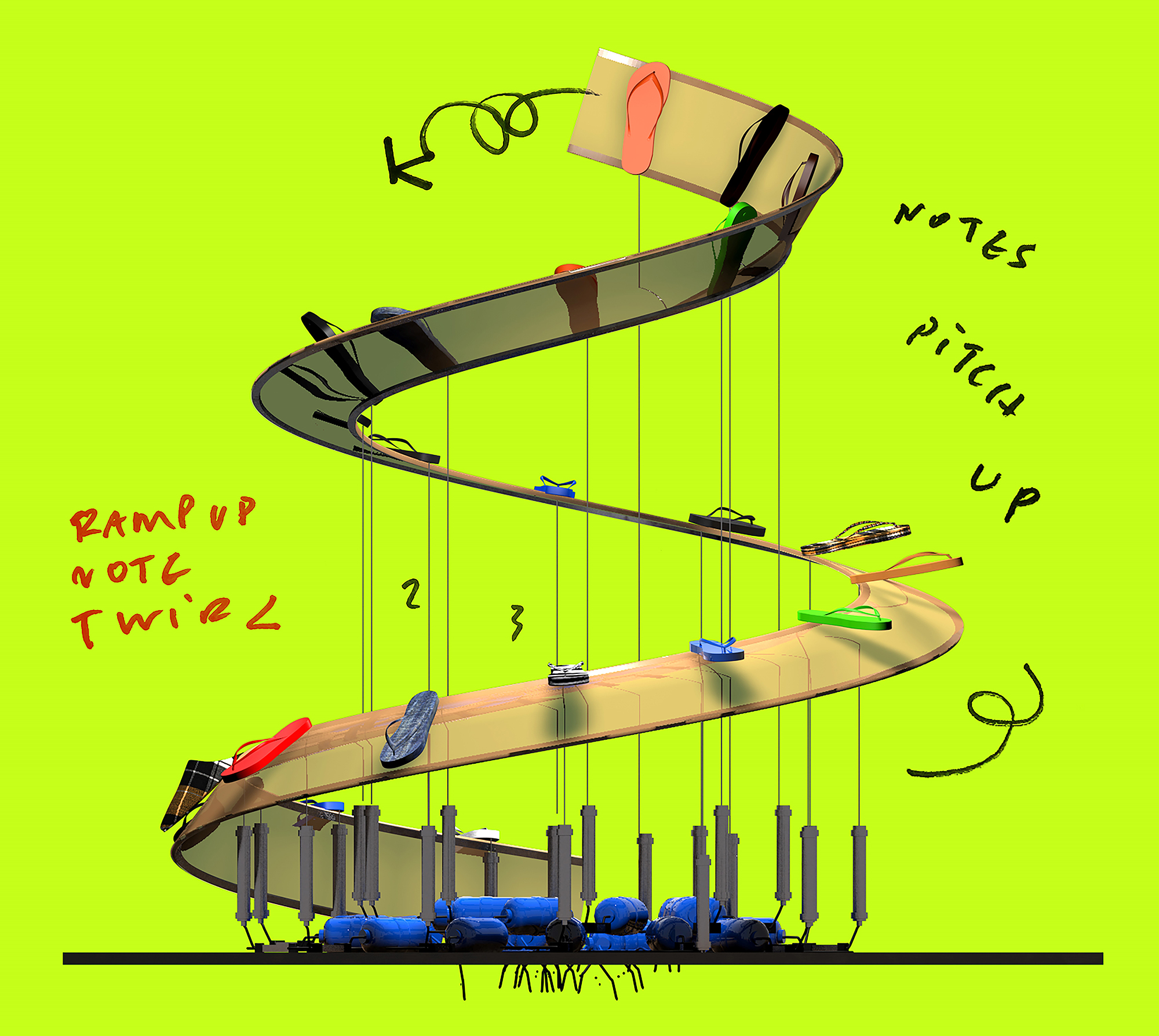

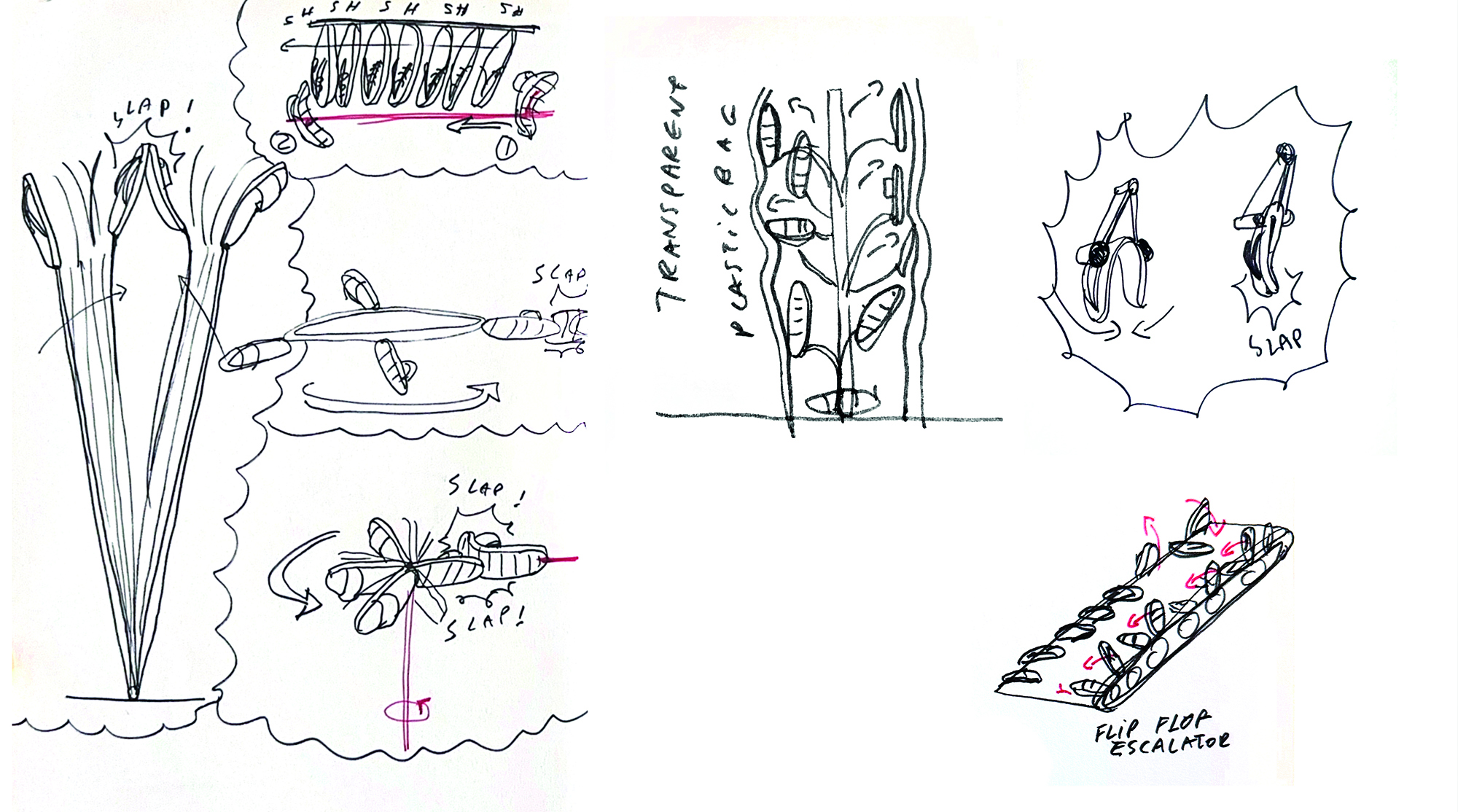

Research for Sole crushing, 2024

Courtesy: the artist and Fondazione Prada, Milan

Meriem Bennani

and Orian Barki in conversation

CURA. 43

Coming of Age

All images:

Orian Barki, Meriem Bennani, John Michael Boling, Jason Coombs, For Aicha, 2024 (video stills)

Courtesy: the artists and Fondazione Prada, Milan

ORIAN BARKI is a documentary filmmaker based in New York. Her animation series 2 Lizards was acquired by the MoMA and the Whitney Museum for their permanent collections and by other private collectors. Orian is currently co-directing her first animated feature, with Meriem Bennani, which premiered in October 2024 at Fondazione Prada, Milan.

MERIEM BENNANI (b. 1988, Rabat, Morocco) lives and works in Brooklyn. Solo exhibitions of her work have been held at: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; MoMA PS1, New York; Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris; The Renaissance Society, Chicago; Nottingham Contemporary, Nottingham; The Kitchen, New York, among other venues. A major solo exhibition opens in October 2024 at Fondazione Prada, Milan. A selection of her participations in group exhibitions include: Whitney Biennial, New York; Geneva Sculpture Biennial; Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement, Geneva/Turin; Shanghai Biennale; Munch Triennale, Norway; The High Line, New York; Centre Pompidou, Metz; Palais de Tokyo, Paris.