Text by Josephine Pryde

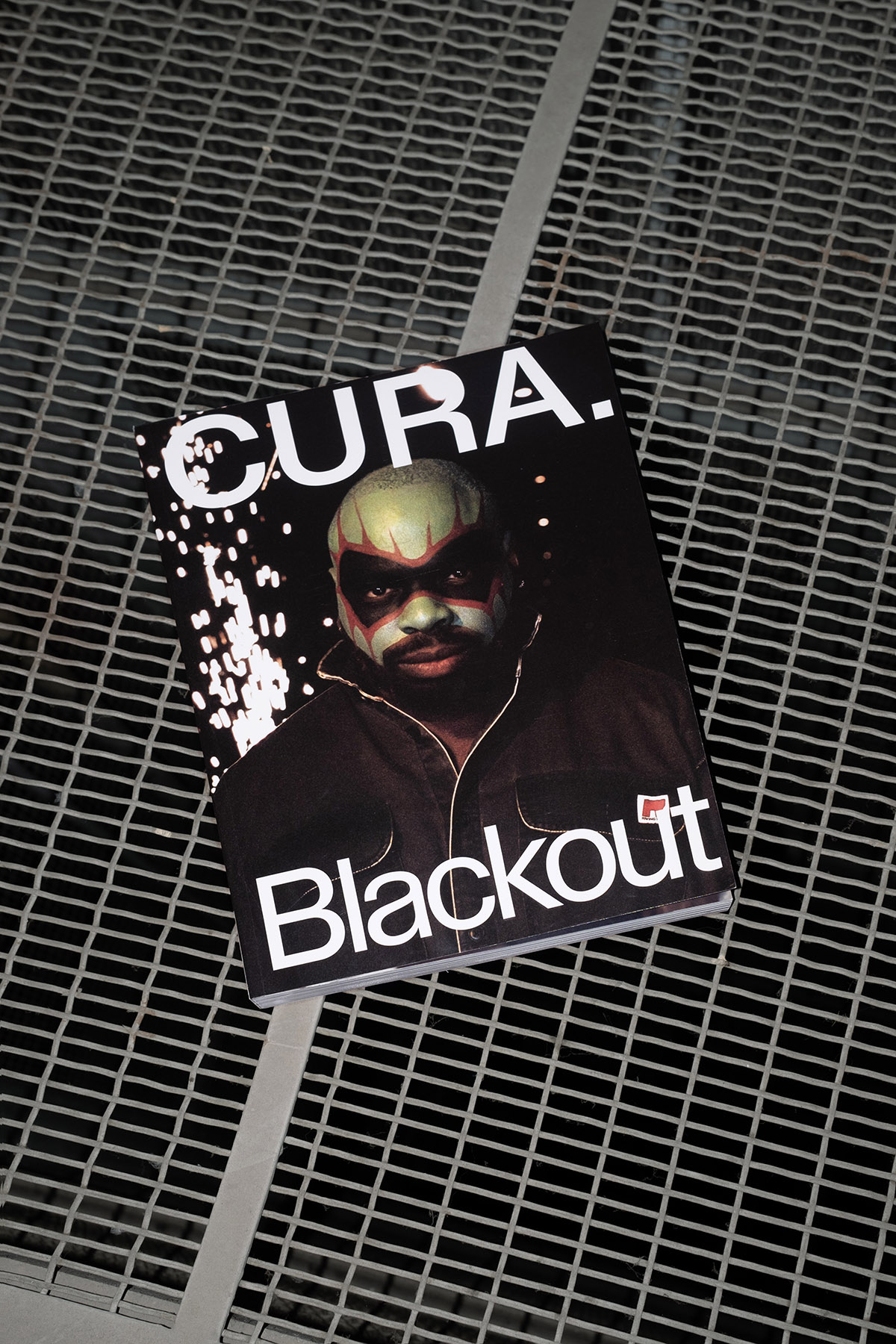

CURA.45

The Blackout Issue

COVER STORY

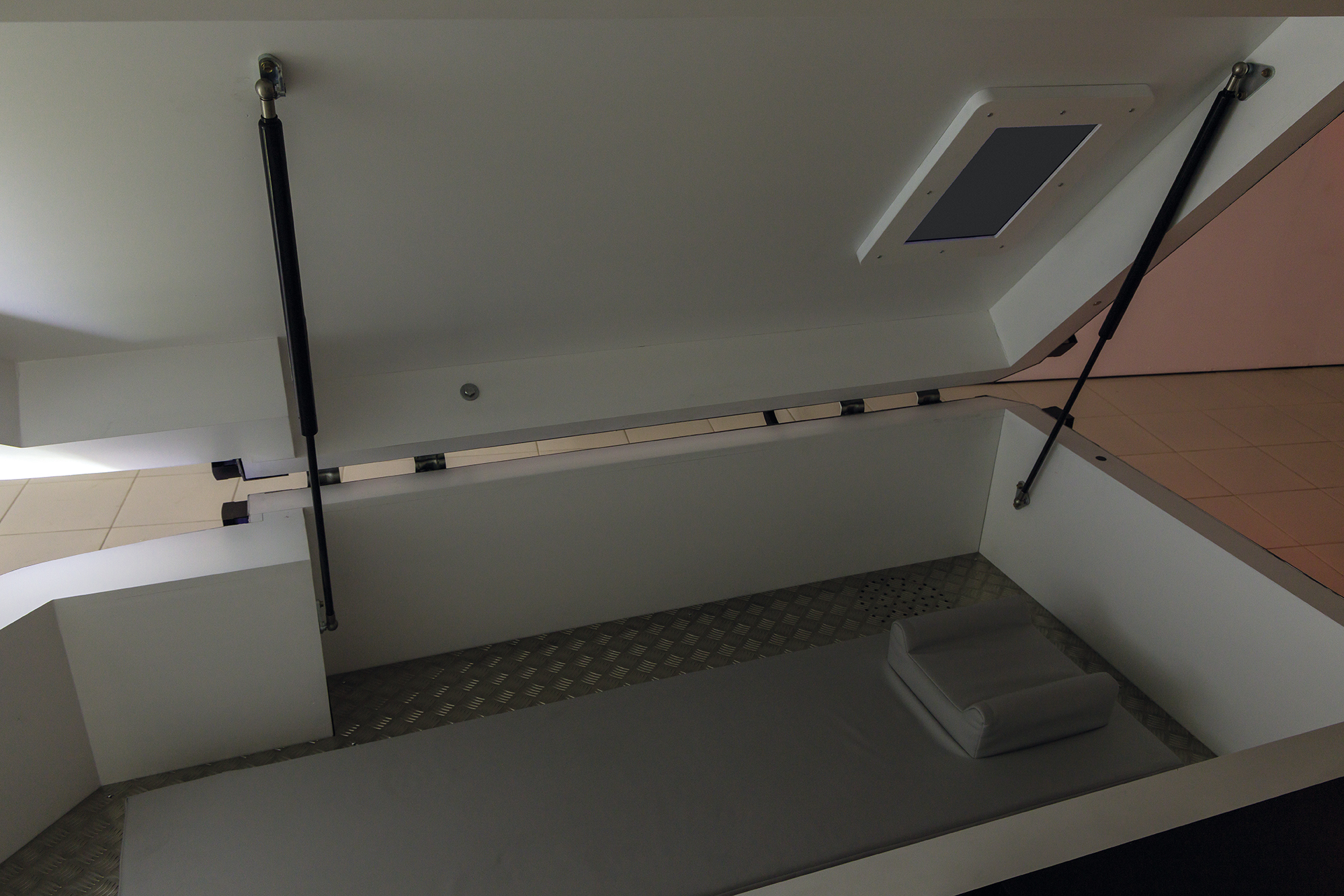

101 Hour Psycho, installation view, Cabinet gallery, London Photo: Mark Blower

Courtesy: the artist and Cabinet, London

101 Hour Psycho, installation view, Cabinet gallery, London Photo: Mark Blower

Courtesy: the artist and Cabinet, London

101 Hour Psycho, installation view, Cabinet gallery, London Photo: Mark Blower

Courtesy: the artist and Cabinet, London

101 Hour Psycho, installation view, Cabinet gallery, London Photo: Mark Blower

Courtesy: the artist and Cabinet, London

I am reviewing the material that R.I.P. Germain has forwarded to me in preparation for writing this article. Everything Relates Back To Drug Dealing is the title accorded to an installation piece shown as part of his exhibition Shimmer at Two Queens, Leicester, in 2022. I notice my name under this artwork’s list of materials. It comes right after the first substance listed, ‘spray paint’. My name has been included in connection to the tag ‘DEJA-VU’, which R.I.P. Germain has added to the wall of a re-constructed convenience store in Everything Relates Back To Drug Dealing. DEJA-VU is here a scaled-up replica of a tag on an earlier artwork of mine, a miniature train called The New Media Express. I had asked the graffiti artist Haka to spray this train with signs I selected, as well as signs he selected, before it was first exhibited in Bristol in 2014. Haka did some great work with his signs and mine. DEJA-VU was one of mine.

Déjà-vu.

Thank you for the credit, R.I.P. Germain.

When I first started to think more explicitly about time and the fracturing of bodies, the relay of images and the simultaneity of broadcast transmissions, in the latter half of the 1980s, I learned a little video editing and experimented with cameras. I did some writing, where I thought about déjà-vu, particularly about the glitch which comes with being in someone else’s déjà-vu, the weirdness of that, the everyday weirdness. You are out with your friend, and they suddenly exclaim, “oh, I am having a déjà-vu.” Your being implicated in their déjà-vu, rather than having your own, lends you a projected sense of your own doubling, one which lies beyond the déjà-vu’s usual impression of you being the one to whom ‘this happened before.’ It is as if you receive, courtesy of another human being’s psyche, a brief glimpse of yourself in a parallel reality, right there, beside yourself. The Oxford English Dictionary offers “tedious familiarity” as one part of a definition of déjà-vu, and quotes A. Koestler for an example of usage:

“A dream-like feeling that he has had this nightmare before.”

I have to learn dialogue trees [game-play mechanic used in role-playing video games] that will get me out of danger… I know how to diffuse my perceived potential threat in a way that puts people at ease but is quite fracturing for myself as a person. I have had to accept that I have to operate “turned-off.” I can’t be as exuberant as I would be, because my physicality scares people just through existing.

(R.I.P. Germain in conversation with Hannah Black, Spike 84, Summer 2025).

He makes no bones about senses of fracturing he experiences as a Black man; experiences that furthermore could be tagged as “tediously familiar.”

***

The photograph Delroy (A) (2018) by R.I.P. Germain is in front of me. It is shot inside, in a studio situation with an improvised feel. It messes with the orthodox studio procedure of the personality facing the camera. The backdrop is of a fabric that has not been ironed or steamed. It is creased, a bit baggy, turquoise. The light falls in patches. The focus in the shot allows light to split color on the film and blur across the grain. There is a pool of shadow bottom left. The figure pictured turns a little bit away from the shadow, slightly left of center in the square frame. I say “he.” Light is directed from the right of the shot and falls on his back, where the camera’s focus illuminates in particular detail a patch of the weave of the navy-blue sweatshirt material he is wearing. Delroy (A) shows his back to the light. In the shallow depth of field, it is only here that become visible those sorts of intense textural details for which sharp-eyed lenses are supposed to be hungry. For the rest, the image is technically sharp, but within this, also softer, while the silhouette remains strong. We are not assaulted with haptic surface conveyance of the sort for which the hyped-up reality of the newest phone camera strives. The sense of detail for the viewer is transferred into taking in the form, the colors, the mood, the shifts, in this photographic subject.

I realize I am spending some time in order to describe a single photograph. A photograph also can be ‘seen’ very fast, in an instant.

I think the stopped motion of the photograph can provoke a deep and visceral experience for a viewer, and that variously scaled printed objects can interpellate people’s bodies into images in really complex and rich ways.

(Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa in conversation with David Campany, Indeterminacy: Thoughts on Time, the Image, and Race(ism), 2022, MACK, p. 46).

In Delroy (A), the facial features that relay the senses—eyes, nose, mouth—are covered or guarded, goggled and shielded. Altered. Black skin holds a turquoise lit mouth-shield. Behind this face stretches the hood of the sweatshirt. Rather than covering any part of the face, the hood is stretched backwards and away from the face, its form stuffed to its fullest into an elongated head. Taxidermy of the hood. What does the pulled-back hood reveal? What manner of studio portrait is this? What manner of subject? Projections made flesh?

This photograph was one of eight in the exhibition Gidi Up (2018), Peak, London, where they were installed hanging on chains from ceiling wires. There were similar solo figures depicted in every one of these images, in various poses, with similarly improvised lighting and studio setting, with similar Alien mother heads. I said “he.” The gallery was further decorated with upholstery and other accessories normally used in funeral parlors. It was a gallery space staged as a funeral parlor. The scene was set within the gallery. Karaoke was done there. Later in his practice, R.I.P. Germain will frequently depart from using the walls of the gallery as somewhere apparently stable enough into which to introduce elements ‘from’ or ‘reminiscent of’ another place as part of the staging of the artwork. He will rather start to flip the terms of installing, by dropping his own completely already rendered architectures into the gallery spaces, and then messing with the semantics from there.

As he tells Hannah Black in the interview cited above:

I’m gonna make my own within yours because I’m not interested in engaging with the historical fuckeries that come with it. I’m gonna make my own building and the building will have to deal with my building rather than me dealing with your building. It’s a way of trying to flip the power dynamics.

***

If you have read this far, you will have several times encountered the artist’s name appearing in the text. R.I.P. Germain. How have you dealt with reading that? Have you looked at it, and skipped over it? Have you, on occasion, read ‘rip’ instead of enunciating each ‘R’, ‘I’, ‘P’? Have you used a French pronunciation of ‘Germain’ in your head, or have you read ‘main’ like ‘mane’? Have you read the full ‘Rest In Peace Germain’ to yourself, each time?

I use an old-fashioned search engine to check some background on ‘R.I.P.’ Full pronunciation, non-abbreviation: rest in peace. Conveniently for the acronym, the same in the original Latin.

Requisecat in pace.

Who is the addressee? The addressee is Germain. R.I.P. Germain moves from exhibition to exhibition, making work under this proper name, under this command, to rest in peace.

Command too strong a word?

A wish. It signifies a wish. A strong wish. Each time I have typed R.I.P. Germain, I have moved my fingers three times, in my slow single-finger typing, to get the capital letter, to get the full-stop, and implicitly wished R.I.P. Each time I read R.I.P. Germain’s as the artist’s name, I join an imaginary incantation, not alone. Not in a choir, but not alone. Different times of enunciation, same name. It is not an instruction, exactly. Not a score. No one can read or speak this artist’s name without uttering this phrase, this gentle, firm, violent imperative, addressed to one deceased. Rest in peace, Germain. The words go over you. The ‘meaning’ that circumvents the bald rules of grammar here, while retaining a clear sense of form and horizon, is perhaps in part analogous to the patch of sharpness in the photograph described above, acute, amidst an apprehended light and figure, but senseless on its own. A conversion of what goes under the proper name has been achieved. The artist and his work go under it. There is no controlling what goes under it. Here, we are not dealing exactly with the mutations in rule-making, grammar, and score that are sometimes said to undergird conceptual art practice. Or rather, the instructions of, for example, Yoko Ono, may have been taken up, but now incorporated, crystallized into a name and a wish, a strong wish, expressed in a quotidian, a daily, repeated sense, one that encourages a collective renewal of the desire to survive, the joy of loving, the imperative to mourn, the imperative to speak of the dead. R.I.P. Germain’s work will not be reduced to the rules of installing inside an architecture that already exists. It will explicitly push to make space for, for example, Black mourning “in a world aggressively indifferent to [our] safety” (Dead Yard press release, 2020). It will insist on an art that can continue to make distinctions while challenging operational limits, it will insist on an art encouraging coherence without sacrificing complexity.

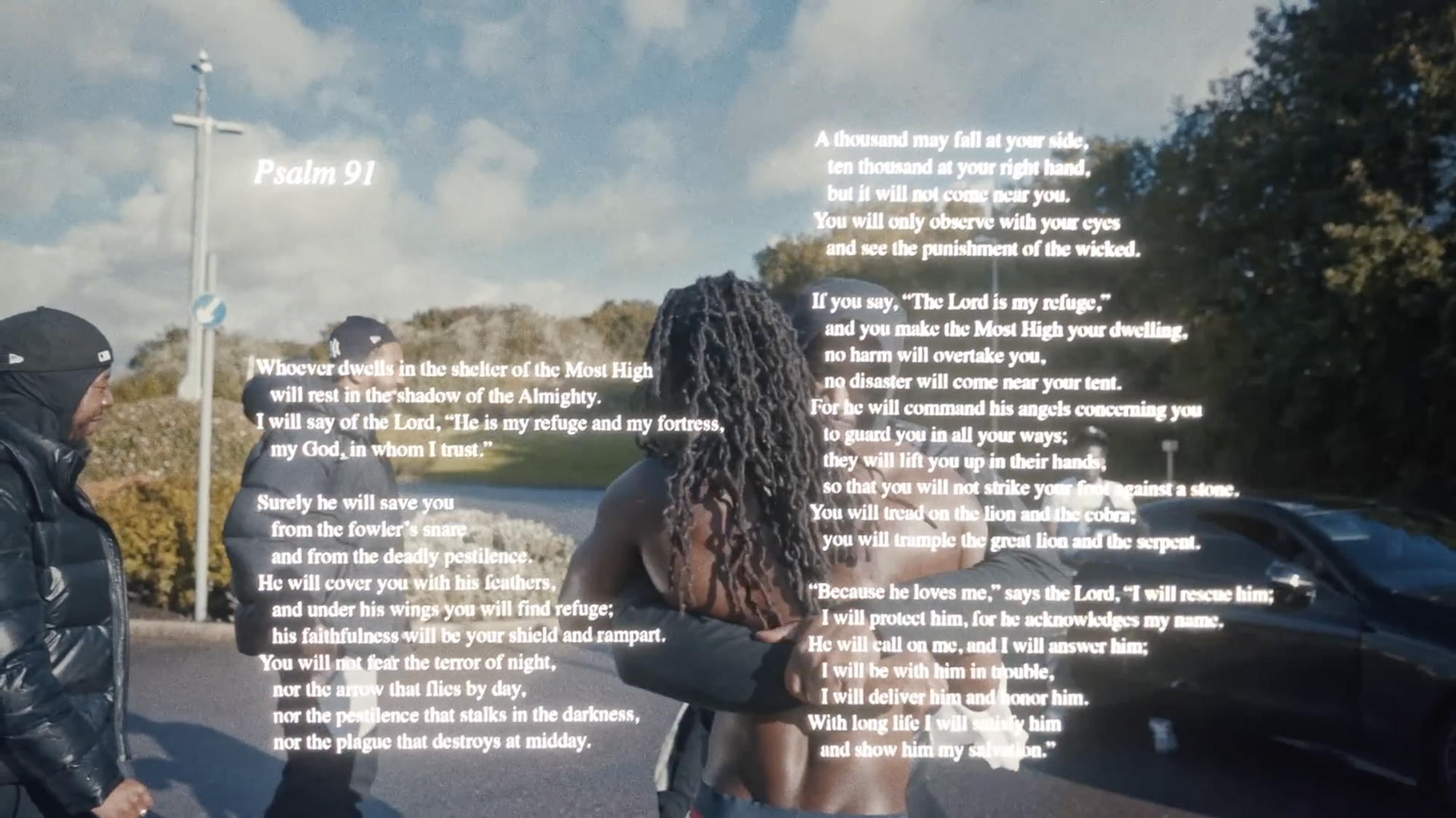

A Saaarf Demo, 2022 (still) Courtesy: the artist

Two Heavens, 2024, installation view, After GOD, Dudus Comes Next!,

FACT Liverpool, 2024 Photo: Rob Battersby Courtesy: the artist

What Does A Hat A Trophy And A Fish Bowl Have In Common?, 2025 (detail)

Photo: Jack Elliot Edwards Courtesy: the artist

What Does A Hat A Trophy And A Fish Bowl Have In Common?, 2025 (detail)

Photo: Jack Elliot Edwards Courtesy: the artist

What Does A Hat A Trophy And A Fish Bowl Have In Common?, 2025 (detail)

Photo: Jack Elliot Edwards Courtesy: the artist

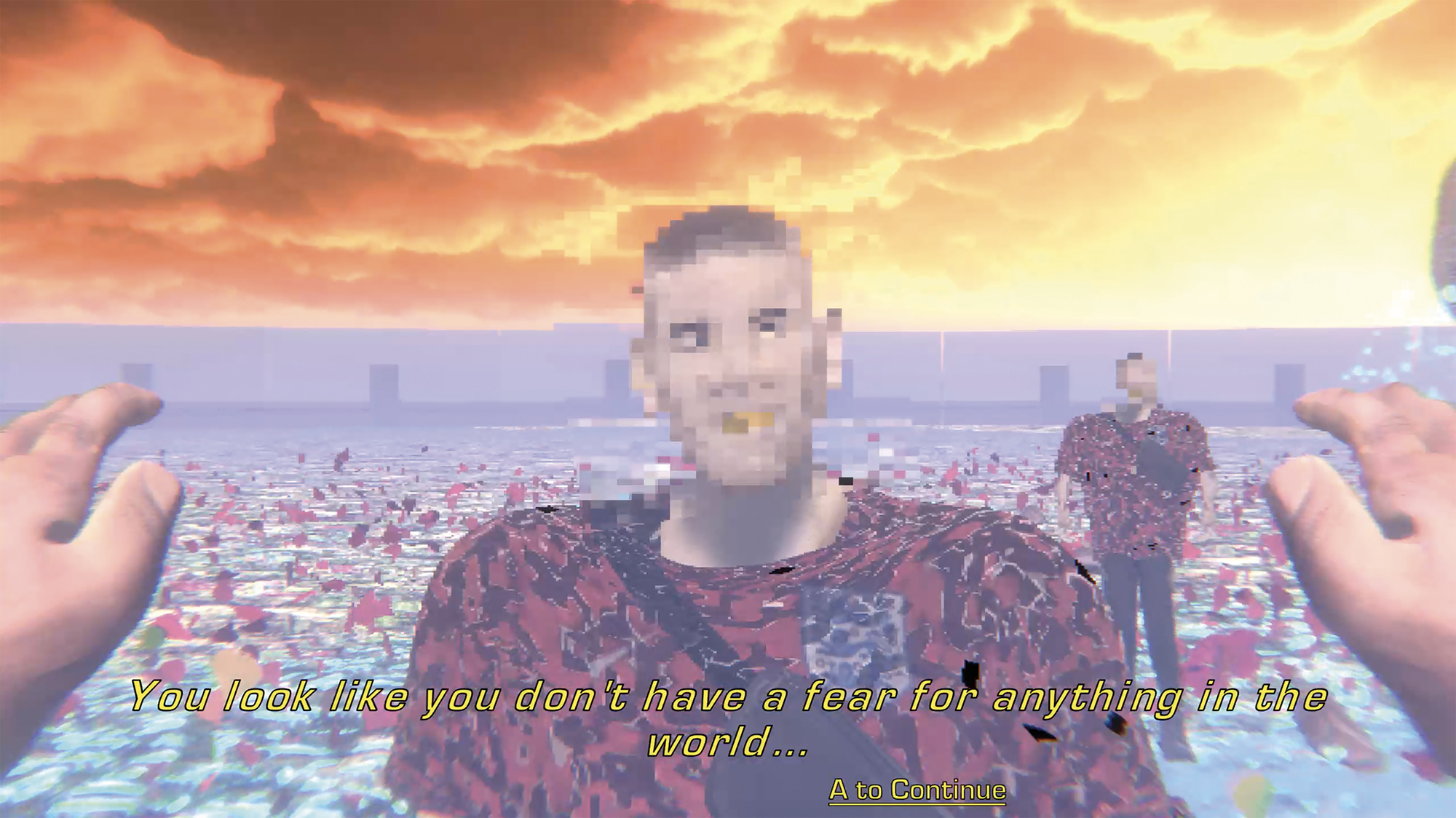

Play Dead, 2025 (stills) Courtesy: the artist

Play Dead, 2025 (stills) Courtesy: the artist

Play Dead, 2025 (stills) Courtesy: the artist

Play Dead, 2025 (stills) Courtesy: the artist

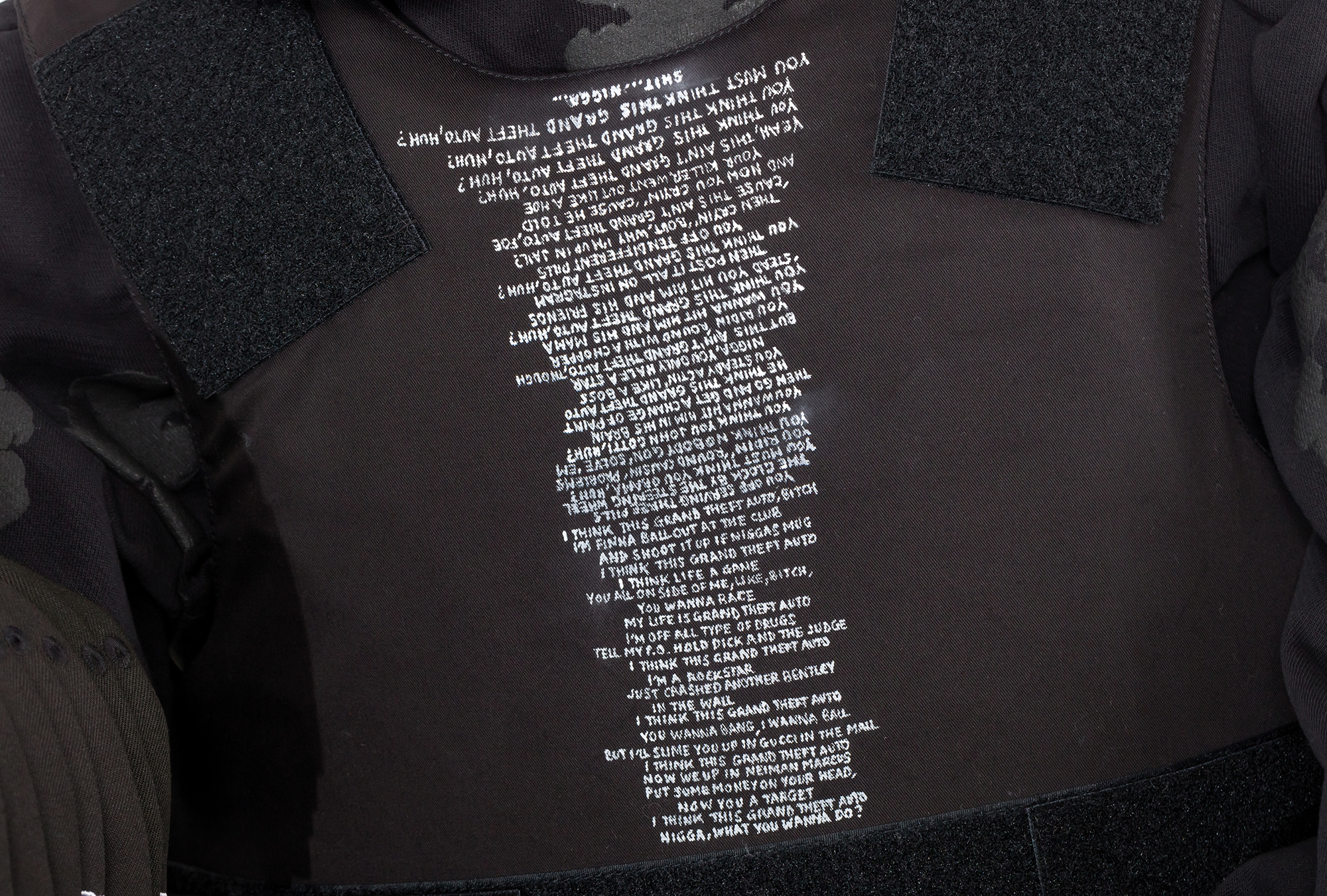

Silent Weapons For Quiet Wars (Build & Destroy), 2024

Photo: Charles Benton Courtesy: the artist and Cabinet, London

White Makaveli Mod (Jesus Piece) (Strictly For My N.I.G.G.A.Z. ?), 2023 (detail)

Photo: Mark Blower Courtesy: the artist and Cabinet, London

R.I.P. Germain

Portrait by Tsarina Merrin Stylist: Ksenia Sharonova

Produced by CURA. © 2025

R.I.P. Germain

Portrait by Tsarina Merrin Stylist: Ksenia Sharonova

Produced by CURA. © 2025

R.I.P. Germain

Text by Josephine Pryde

CURA. 45

The Blackuout Issue

Cover Story

R.I.P. GERMAIN (b. 1988, Luton, UK) lives and works in London. His practice is anti-didactic, sitting instead in a baggy space of iteration, loose attempts at classification, description and discussion that remain resistant to comfortable moral certainties, or stable meanings and values. Demonstrating an application of the tools and logics of artmaking, and the development of a visual language applied to topics that are routinely flattened, R.I.P. Germain seeks to unpick and analyze, and provide some cognitive space around the hyperobjects of Black culture. Suspicious of stable meaning making, R.I.P. Germain’s interests lie with uncovering things that may be uncomfortable, while resisting the urge to over explain or claim authority. The multidimensionality and possible inversions of perspective inherent in the work are then techniques to question where privilege lies, and ask us to personally examine our subject position and how we might have arrived at the place we have.

JOSEPHINE PRYDE (b. 1967, Alnwick, UK) is an artist who lives and works in Berlin.