Text by Nicole Yip

CURA.36 SS2021

FUTURITY

A sharp inhalation

.

.

.

A long slow release.

Only darkness as the sound of breath swells around the room. A silent directive appears on-screen, turquoise text on black: “take a deep breath.” Then without warning, we are plunged underwater, plumes of frothing waves overhead.

This opening gesture orients us for the journey to follow in Alberta Whittle’s 2019 video, between a whisper and a cry: a ride on the high seas through ‘the weather’; being submerged within a wave, then coming up for air. From this quiet beginning, Whittle’s invocation opens up a search for other bodies, other breaths, across a shared spatiality. A heightened awareness of what is held within our own body is kindled. These kinds of relational spaces, which implicate us in the labor of feeling with and through others, are a hallmark of the Barbadian-Scottish artist’s films, sculptural installations and performances. They are spaces often foregrounded by painful historic truths, unsettling any position of privilege or passivity; they are at once spaces of rage and reckoning, of empathy and hope.

What then unfolds in between a whisper and a cry is a month-by-month movement through the hurricane season, following the thrust of a colloquial rhyming verse from the Anglophone Caribbean. From June (“too soon…”) to October (“all over”), it draws on Christina Sharpe’s notion of ‘the weather’—that is, “the weather inaugurated by slave ships, over 500 years of them”—to remind us of the precarities of geography, of how environmental catastrophe and the legacies of empire are so deeply entangled. Here, as elsewhere, Whittle crisscrosses the Atlantic, from the gallant architecture of Glasgow, to the sunbaked mangroves of Senegal to her native Barbados, retracing how power moves and manifests across geographies. In traversing a deep history of transoceanic captivity, she registers the frequencies of black lives that continue to be under siege, hundreds of years after those ships left our shores.

Celestial Meditations V, 2018

To fully discern the weight of Whittle’s work requires an understanding of the context of Scotland (where she has been based for over two decades) and its troubled relationship to its own history. Until recently, Scotland benefitted from what Whittle has termed “the luxury of amnesia”: a convenient erasure of its shameful complicity in the triangular trade, even though the material products of its colonial wealth are still plainly visible in its architecture. It is no coincidence that Whittle has sited many of her films and performances in such spaces haunted by the specters of their pasts. Whether a manor house of the mercantile elite or a former tobacco store, these are spaces in which black bodies have been both invisible and hyper-visible. Not surprisingly, Scotland’s collective amnesia has also had grave implications for the presence and visibility of Black artists based there, both historically and in the present, but critical voices such as Whittle’s have been a revitalizing force in their recuperation.

How then, does one begin the work of reclaiming the experience of those erased by the efforts of history, of those kept outside or below representation? In many ways, Whittle’s practice is a relentless search for a form of refusal of these ongoing vicissitudes of ‘the weather’, using the black body itself to locate ways of being that are not captive to the present terms of order. Through an array of performative strategies, enacted by the artist herself or a close-knit cast of ‘players,’ Whittle visualizes the body’s capacity to manifest what Tina Campt has called an “anti-gravitational black flow.” We see the body, deformed as it is by the pervasive contours of racism, defying the physics of anti-blackness: the body rising, resilient, intrepid.

New Valentine, 2017

Between a Whisper and a Cry, 2019Between a Whisper and a Cry, 2019

Between a Whisper and a Cry, 2019

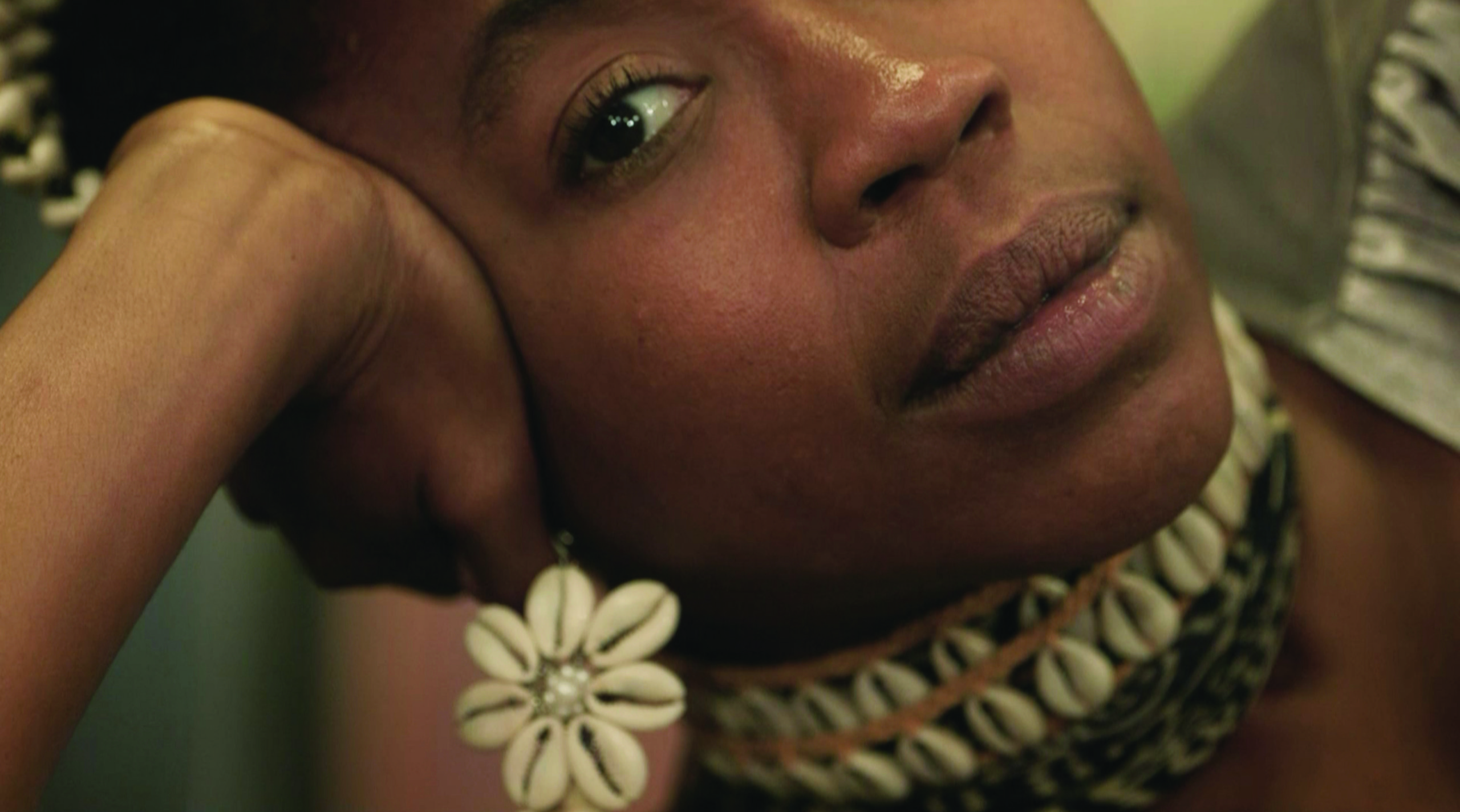

In A study in vocal intonation (2018) we see the body majestic, as ancestral memory confronts veiled histories in a performance that forms the central axis of the film. Brandishing a large cane knife in each hand, Whittle moves regally across the neoclassical hall of Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art, originally built as a private mansion of Scotland’s sugar aristocracy. Elsewhere, the body seems to perform a kind of resurrection, as in her most recent film RESET (2020), an elegy to a year of black loss and mourning. Here, one of the central figures is that of choreographer and performer Mele Broomes. Adorned in an armature of seagrass and shells, her posturing shifts between the statuesque and the glitchy, yet her trajectory and gaze are always turned skyward. The irrepressible vitality of black life is echoed in the montage of found footage that cuts through these filmed sequences: newsreel of worldwide protest and rebellion captures bodies in uprising; recurring images of a serpent evoke the mystical ouroboros, ancient symbol of eternal renewal; a man performs the limbo, a symbolic dance that originated as a Trinidadian funeral ritual, while also recalling the bent bodies of slaves as they entered the hold of the ship.

RESET is a complex meditation on what it means to feel and heal, conjuring a remembrance of the relationship between our embodiment, and individual and ancestral experiences of trauma and oppression. The affective experience of Whittle’s work is shaped as much by her visual virtuosity as by her interest in sound, language and the voice. Inspired by Paul Gilroy’s ideas of antiphony, Whittle summons voices, ancient and spectral, familiar and intimate, in a “call and response with the blood waters of my body.” The words of writer and collaborator, Ama Josephine Budge, offer a kind of score, weaving an intricate polyphony into the textual layers of the film. Shifting soundscapes imbue the film with a profound, yet subtle, emotionality—from a mournful procession of stretched-out drones to the haunting arrhythmia of a pulsating off-beat thrum.

Made in the incipient wave of a deadly pandemic, business as usual: hostile environment (2020) reaches its apex in song, finding catharsis through the voice in waves of soaring expression. The film traces an abbreviated genealogy of state racism and all its pathologies: an ongoing state of exigency that has rendered the environment hostile to black lives. Passenger ships arriving from the Caribbean, the insignia of white nationalism, the Windrush scandal, the bias of a malignant immigration system, the disproportionate toll of Covid-19: the chokehold on black life tightens in Whittle’s summation of images. And then, in what might be understood as a sonic articulation of “anti-gravitational black flow,” comes a release:

.

.

.

The frame cuts in around the mouth of a singer, her image doubled and mirrored. A voice, raw and powerful, soars over skittering drums; the voice as shaped sound, unmaking and remaking spells of meaning in an alternate vision of black futurity.

Amazing Grace I, 2020

CURA.36

Spring Summer 2021

THE FUTURITY ISSUE

CREDITS:

All images Courtesy: the artist

and Copperfield, London

ALBERTA WHITTLE (b. 1980, Bridgetown, Barbados) was awarded a Turner Bursary, Frieze Artist Award and a Henry Moore Foundation Artist Award in 2020. Alberta is a PhD candidate at Edinburgh College of Art and is a Research Associate at The University of Johannesburg. Her creative practice is motivated by the desire to manifest self-compassion and collective care as key methods in battling anti-blackness.

NICOLE YIP is Chief Curator and Head of Public Programmes & Research at Nottingham Contemporary. From 2016 to 2019 she was Director of LUX Scotland, and previously worked at LUX, London, Firstsite, Colchester, and ICA, London. She has curated exhibitions and projects at venues including: Tramway, Glasgow; Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow; National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, Nassau; Kochi-Muziris Biennale; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Firstsite, Colchester; The Showroom, London and ICA, London.