Text by Whitney Mallett

“Let’s choose to be denigrated. Give your ass for nothing. Make it mean nothing. Just soulless flesh.” Catherine Breillat, Of the Collector’s Good Pleasure (translated from French by Julien Ceccaldi)1

The centerpiece of Julien Ceccaldi’s solo exhibition Gay (2017) at the New York gallery Lomex was a grand tableau of a dozen naked men idling around a bathhouse. Your eyes first fell on a bulky hunk in the center foreground. The slant of his beefy shoulders and the way his weight is lackadaisically settled into his right leg, with its popping calf muscle, it’s clear his gait is slow and confident. There’s a shorter, skinnier, balder man behind this Adonis. He’s reaching his leg forward in the midst of tying a towel around his waist, betraying a sense of urgency and an exaggerated stride. The eye is first drawn to these two figures because they’re in motion, but it’s further back in the painting amid the brawny butts and lounging legs that your gaze settles on another body with a receding hairline and furrowed brow. It’s immediately clear this anxious man peering out from behind a pillar is the intended vessel for the viewer’s subjectivity. Everyone knows what it’s like to feel how this character looks.

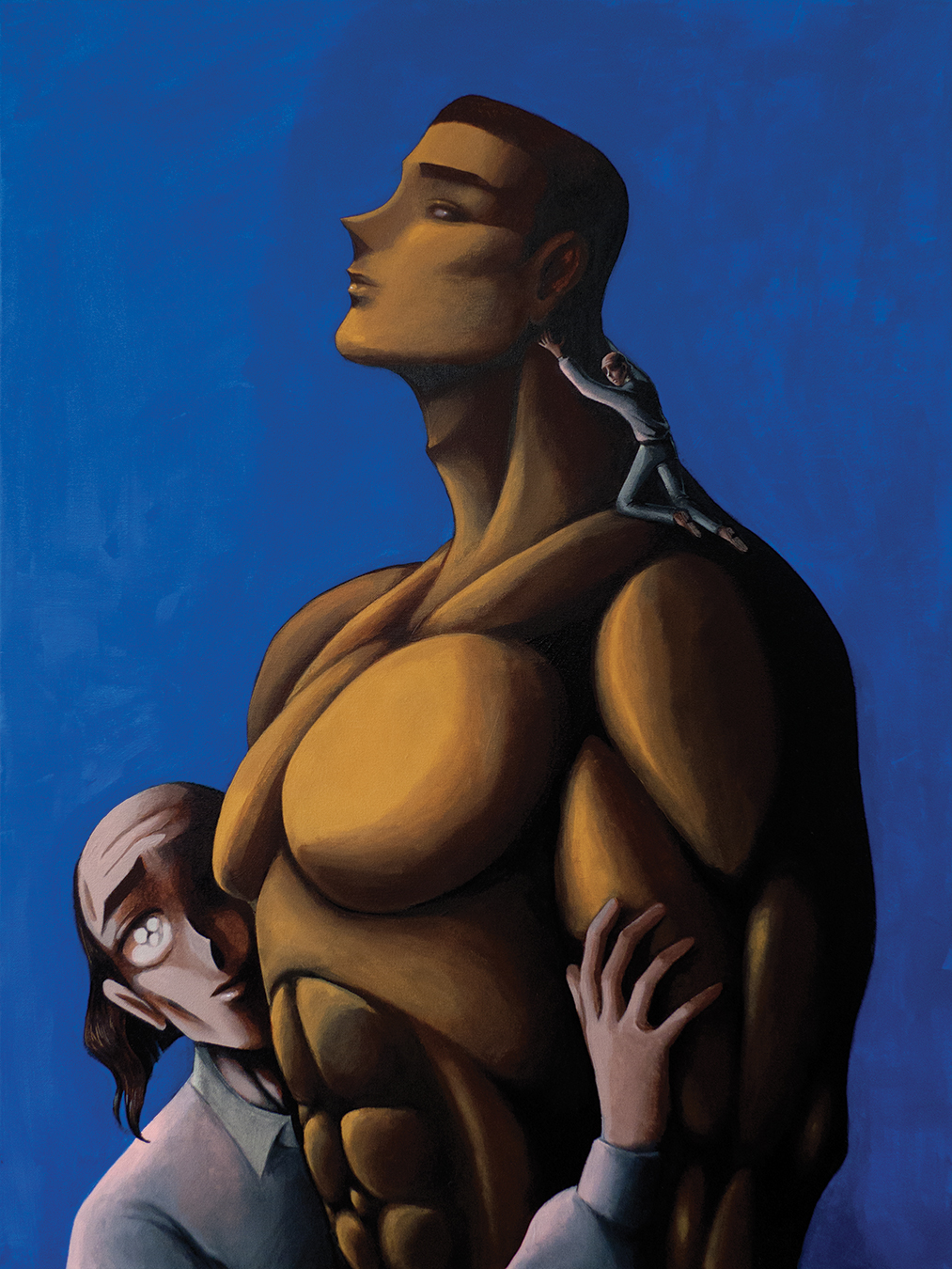

Ceccaldi’s characters regularly look how they feel inside. The boundaries of their bodies are at the whim of extreme emotional states, and scale is frequently psychological hyperbole. Ceccaldi paints eyes like two big black holes, a pair of windows to a vapid soul. Or he writes a comic where the protagonist is disproportionately smaller than his crush. But this accordance of looking to feeling results in a discord between how we see ourselves and how others see us. It’s surreal but also realistic. In a room full of naked bodies, every single one can feel like the guy nervously peering out from behind the pillar, but to one another, look like just another dude casually strolling by with a towel tied around his waist.

There’s a deep existential loneliness in Ceccaldi’s work that becomes transmuted into cute Pop art. Manga—specifically the teen-girl subgenre Shōjo—is the biggest influence on Ceccaldi’s approach to illustration. Borrowing these comics’ turned-up noses, multi-tone shading, and flower motifs, he echoes their penchant for wrapping up angst and Weltschmerz in pretty packages. It reminds me of how it feels, when you’re heartbroken, to walk around in the rain, your headphones blasting the perfect breakup track, imagining the tragic music-video version of your life.

Ceccaldi grew up with Shōjo, watching TV shows like Sailor Moon and The Rose of Versailles and reading comics like Moto Hagio’s Heart of Thomas and Shigeru Mizuki’s NonNonBa.

He developed his technique drawing fanart on Oekaki boards, online forums where you could only post images created with the website’s app. Other obsessions inform Ceccaldi’s tone and sensibility—like the Gilmore Girls TV show and Catherine Breillat movies—but his teen years spent perfecting these manga drawing techniques mean they’re the most natural way for the artist to interpret his life into narrative form.

Growing up, Ceccaldi drew slim young women like the protagonists he most related to. But when people started to think these illustrations represented the object of his desire, he switched to drawing women popping with muscles instead, a mix of what he related to and what he wanted. For several years, Ceccaldi painted these hunky women on wearable clothing that was shown in galleries in New York and Berlin. He would make these muscular femmes the star of four-panel comics that appeared regularly in Sex Magazine and one graced the cover of ArtForum Summer 2014. About a year later, he shifted to painting more on traditional canvases and the content was frequently androgynous figures in triangulated interpersonal tangles. More and more in Ceccaldi’s work, there are skinny men pining after roid queens. And there’s skeletons because we can all relate to the dread of existence that we’re going to one day die.

Ceccaldi told me about this reality TV show from 2009-2010 called Tool Academy. A cast of muscular dudes who are total “tools” learn to be better people and partners. During the elimination ceremonies, they’re always shirtless with puffed out pectorals. On one episode, the contestants all had to draw self portraits. A few of these big brawny men drew the saddest little stick figures. It can provoke disassociation the way bodies and their avatars are on display for selection at nightclubs and on apps. You don’t have a say in whatever meat suit you’re designated at birth. You can modify it but there’s no Freaky Friday-type swapping or bodiless options available. And our fantasies of what bodies we want to be and what bodies we want to be with frequently intermingle.

Ceccaldi is a self-conscious Romantic. His art is about personal expression and he alludes to this in the work itself but not without some self-deprecation. In Inherited Struggle (2014), the final panel of a four-panel comic shows two muscular women crying so hard that their bodies are melting into puddles of tears while delivering tragi-deadpan punchlines, “I just wanted to artfully express my emotions” and “I just wanted to understand my own despair.” Throughout Ceccaldi’s work, especially his comics, there’s a sincere desire to exteriorize (and maybe also to exorcise) psychic interiority. In Tell Me Less (2013), this tension between inner world and outer expressions shows up in a scene with two girlfriends chatting over drinks. One complains that her gal pal talks too much about her intimacy; however, in accidentally oversharing an intimate secret of her own, she experiences, “the healing power of honesty.”

The desire to externalize and express is compulsive and the result often cathartic but it’s not without stress and strain. And the body is often where this conflict manifests. In I Am Goals (2014), two girlfriends sit at a table with drinks, one wondering if the other’s life is really so “ahmeezing” because her face looks “so sad.” It’s in our body language that we betray the inner feelings we’re trying to suppress. And it’s often what we want done to our bodies in private that leaves us feeling conflicted about what to share and what to keep secret. In Tell Me Less, for instance, the character’s revelation comes from admitting she enjoys being degraded in the bedroom.

Especially in his longer narrative works, Ceccaldi interrogates the adult games we play. The title of his comic books Less Than Dust (2014) and Human Furniture (2017) allude to slave and sub dynamics, but the content of the stories themselves is more mundane than fetish, banal episodes of desperately waiting for a crush to text back or an unhealthy obsession with an unrequited flame. Regularly subjecting yourself to rejection comes with a comforting familiarity if not a twisted pleasure. And transforming these experiences into comedic tales definitely has something to do with finding pleasure in denigration. The feedback loop of living and retelling lets you find agency in situations where you’ve relinquished control. The body becomes both invaluable and totally disposable, the medium for transcendent experiences and a mere prop in an absurd theater of love and misery.

1

Julien Ceccaldi artist talk at 356 Mission,” November 22, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ohmFj8pI9eg.

CREDITS:

All images Courtesy: the artist and Jenny’s, Los Angeles