Fact Structures Amount Structures Language Structures

Esther Schipper, Berlin

March 15—April 13, 2024

Review by Giulia Colletti

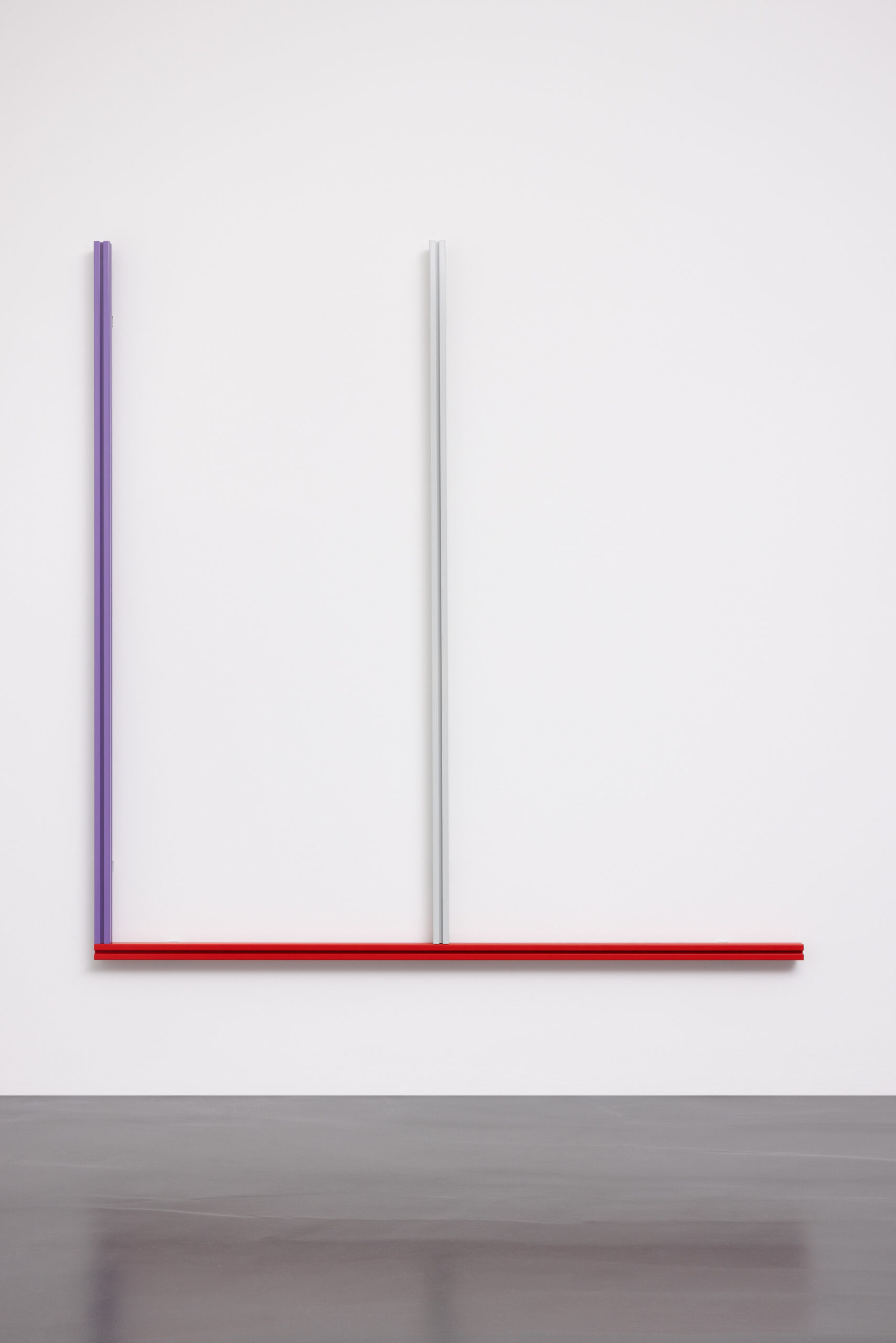

Red Flow Process, 2024

Lilac Fixed Routing, 2024

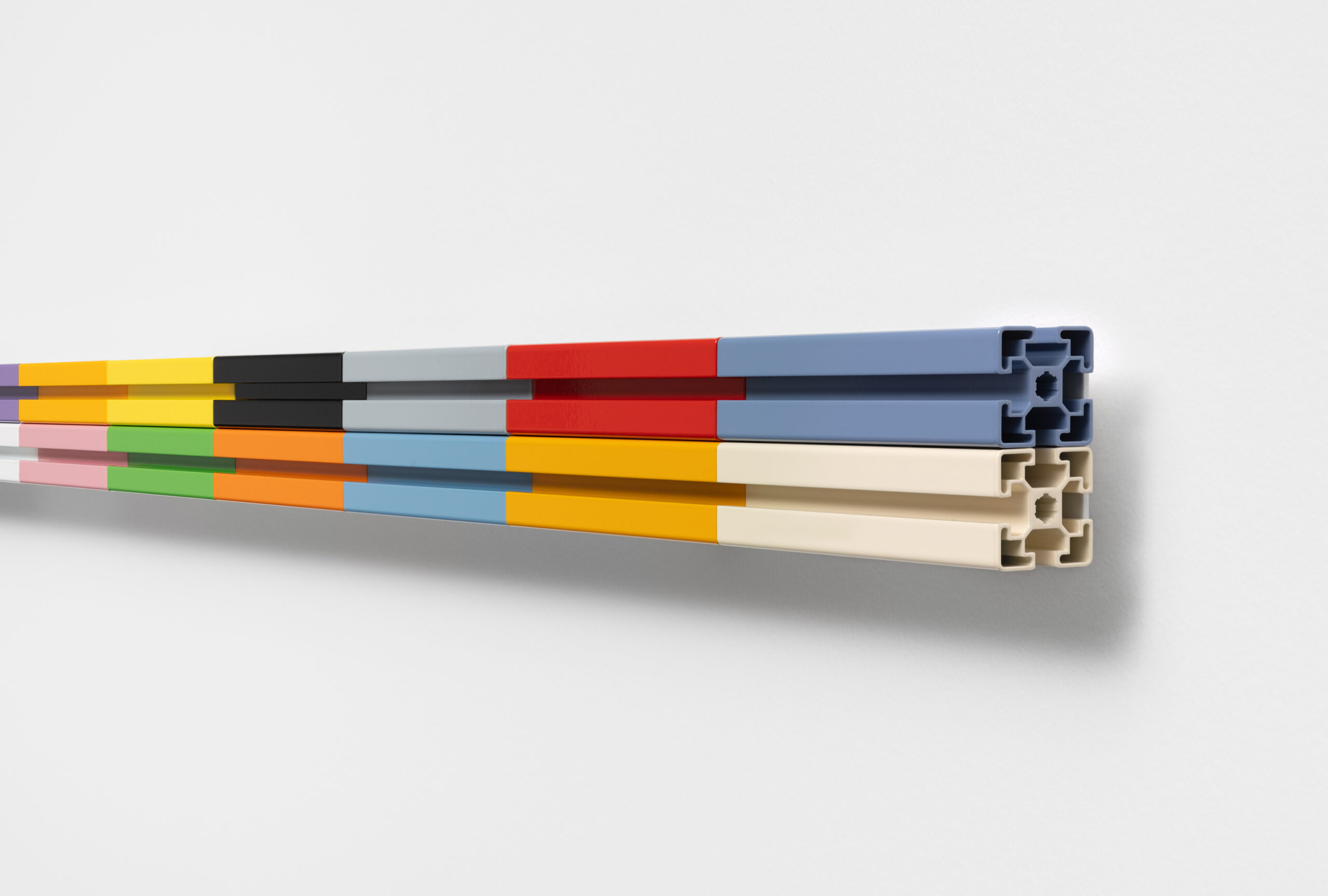

Model of a System Type 2, 2024

When Crash was released in 1973, the shock went beyond the convoluted juxtaposition of sex and cars; it was a revelation of how technology permeates even the most intimate human relations. As novelist Zadie Smith puts it when confronting James Graham Ballard’s novel; not man-as-technology-forming but technology-as-man-forming.[1]

This resonates when engaging with Liam Gillick’s tenth solo exhibition at Esther Schipper. Here, the artist transitions from things added to the world towards seemingly trivial yet uncanny machines, infrastructure, logistics, and production methods. The tubular wall-mounted works are crafted from lightweight aluminum t-slot extensions, typically employed in the construction of laboratory rigs, computer numerical control machines, and advanced production lines. Such mechanical pieces turn into visually captivating abstract works through the adoption of bright colors, infusing them with a sexual allure.

While in Crash body and technology refract through each other by blending carnal abstraction and design, Gillick’s abstraction of forms stems from the functional ‘organs’ of buildings, server farms, hard drives, and circuits. This recent body of work is rooted in the pioneering efforts of philosopher Otto Neurath and artist Gerd Arntz in the 1920s. Their innovative approach, known as the Vienna Method or ISOTYPE (International System of Typographic Picture Education), aimed to simplify the representation of complex statistical information through the development of a quantitative system utilizing pictograms – a prevalent visual language nowadays online. Fostering the democratization of specialized knowledge for mass audiences, the visual lexicon that Neurath and Arntz crafted served as a pedagogical tool. It was designed to diminish the reliance on tradition, custom, and formal education in the comprehension of information. By employing comparative symbols, this visual language not only facilitated understanding but also encouraged intellectual engagement and imaginative exploration. Gesturing to these efforts, Gillick sets aside conventional subjects such as geometry and mathematics to delve into the elaborateness of production processes and the complexities of information dissemination, reflecting on how to effectively communicate such complex ideas.

The production process is even at stake in the design of his exhibitions, for which he undertakes the task of meticulously composing comprehensive models of the venues, notwithstanding its apparent impracticability. Counterintuitively, such a laborious rendering process, reminiscent of industrious endeavor, allows Gillick to immerse himself in the physicality of the space. Through the creation of true-to-scale replicas of the venues and authentic materials, he adopts a pragmatic and programmatic approach to his craft, minimizing the error to maximize the out-turn. This methodological approach seems to give him a sense of confidence with the exhibition settings, enabling him to navigate them with seemingly effortless fluidity. There is a lack of any underlying emotional attachment, desire flow, libido, or impulse; only purely factual models stand.

Gillick appears profoundly influenced by spaces, in particular when dealing with emotionally charged environments, which forces him to confront melancholy, anxiety, and joy. This came out from the artist’s recall of a site visit to a monastery in the Czech Republic, where a chamber housing a venerated relic, the shroud of Christ, presented a distinctive challenge. Instead of allowing the sanctity of the environment to overwhelm his artistic process, he underscored the significance of maintaining clarity and intentionality. By immersing himself in the site’s atmosphere beforehand, it seems he embraces its affective qualities without compromising the creative vision. Such an imposed rationality seems to crash with his creative process, which is deeply intertwined with a chaotic thought. The production process primarily takes place in the virtual realm, using 3D renderings, before moving into the physical exhibition space. By completing a significant portion of the preparatory work digitally, he believes he can better manage the physical environment. But can he truly maintain control?

When addressing his stance in current times, Gillick questions the expectation from artists to constantly reveal their innermost thoughts and emotions, to be transparent about their origins and motivations. In a fascinating contradiction with the control over the production process, his work is not always about truth-telling in the traditional sense. To him, art operates on an abstract level, exploring truths that transcend mere factual accuracy. Such a dichotomy presents the challenge of navigating between societal expectations and one’s own creative instincts. It is a subtle balance, and one that requires a nuanced narration of reality, which entails a certain ambiguity and a paradoxical sense of (un)predictability.

Ultimately, Gillick’s posture seems to respond to Ballard’s urgency; we live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind… We live inside an enormous novel… The fiction is already there.

The writer’s task is to invent reality.[2]

1

Sex and wheels: Zadie Smith on JG Ballard’s Crash, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jul/04/zadie-smith-jg-ballard-crash

2

James Graham Ballard, Crash, New York: Vintage, (ed) 1995, introduction, p. 2.

Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul

Photo © Andrea Rossetti