Text by Massimiliano Gioni

ESSAY

Pipilotti Rist is the only person I know who chose her own name. Though born an Elisabeth, as a little girl she made people call her John or—for a whole year—Pierre, to see what it was like to be male, rejecting the stereotypes forced upon her by anatomy, biology, and culture. As a young woman she instead opted for Pipilotti, a name inspired by the brash heroine of the legendary Pippi Longstocking books.

Like the tales dreamed up by Astrid Lindgren, which were made even more famous by a lysergic TV series that aired in 1969, Rist ushers us into a magical world of vivid colors and constant transformations. It is a place where every wish seems to come true: pure libido, zero reality principle.

From her very first experiments in Super 8 and later in video, Rist has tried to expand technology, making it more organic and in a sense more feminine, but also infusing it with a pantheistic sensuality that reimagines the entire universe as a matriarchal community of neopagan goddesses. This prelapsarian realm is inhabited by red-haired, perennially adolescent creatures, or by smiling provincial valkyries who use flowers to smash car windows under a policewoman’s approving gaze. The mood is redolent of both third-wave feminism and 19th-century Symbolism, angry bad girls and swooning poses. Echoes of Pre-Raphaelite paintings and Gustav Klimt’s beauties float through Rist’s videos, interspersed with scraps of abstract psychedelia and giant close-ups of body parts, sexual organs, or magnified pupils scanning the viewers who lie stretched on the floor below her video installations.

Like Walt Whitman, Pipilotti Rist sings the body electric, imagining a digital Eden where nature and culture are interwoven to form a collective organism that is carnal yet ethereal, voracious yet ascetic.

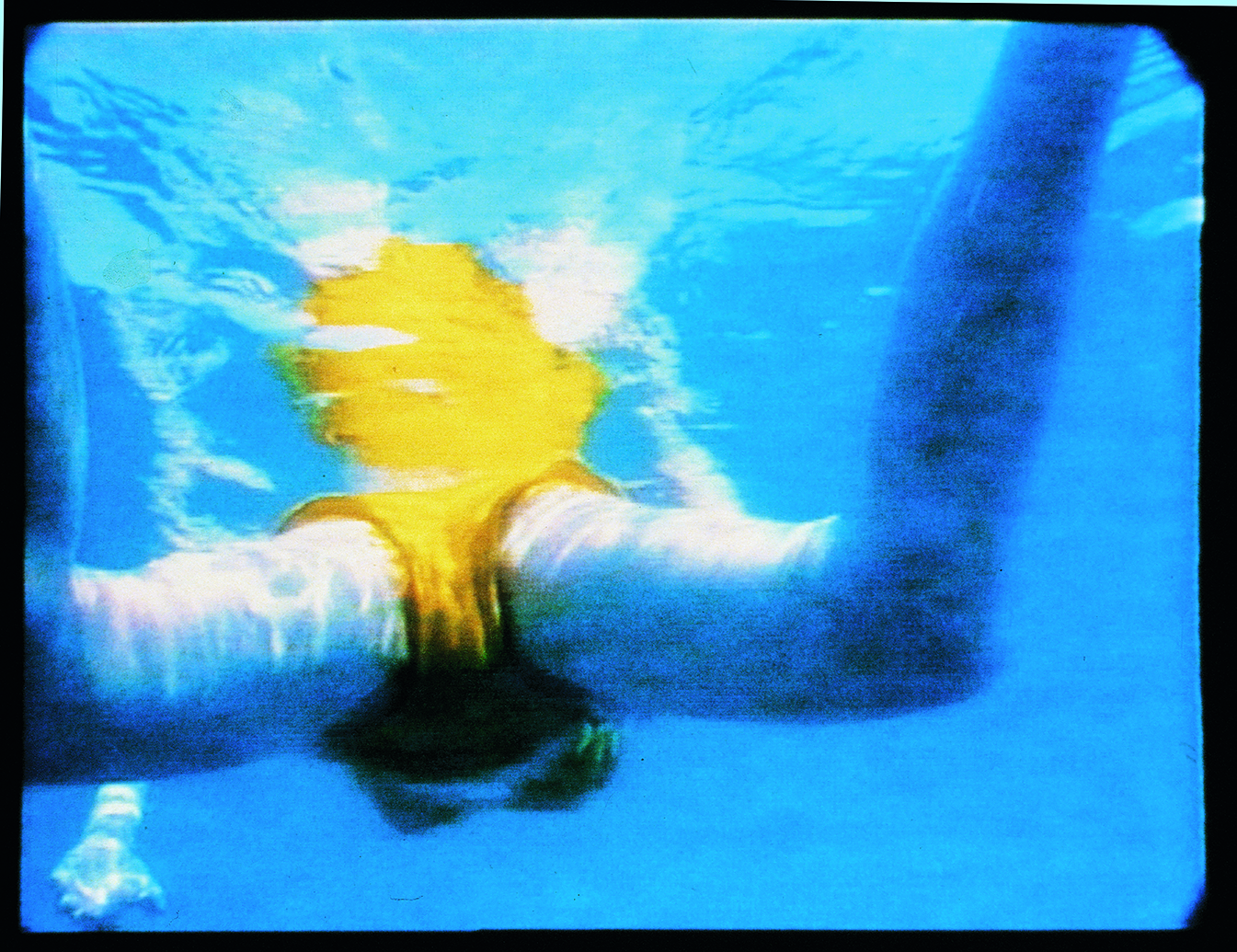

For Rist, our eyes are blood-driven cameras; our brain is the network of madly firing synapses that she depicts as a “pixel forest” in Pixelwald (2016). Rist’s world is liquid and often filmed underwater, as in her famous Sip My Ocean (1996) or the more recent 4th Floor to Mildness, made for her 2016 survey at the New Museum and recently on view at the Louisiana in Copenhagen.

As always in Rist’s work, one can detect many different references to art history—each one subtle, though radically transformed by both digital technology and dramatic shifts in perspective. For instance, looking at the aquatic sequences in 4th Floor to Mildness, one inevitably thinks of Claude Monet and his water lilies, though Rist offers an unwonted angle below the water’s surface in an inversion that is characteristic of her work. Rist often avoids placing her camera at eye level, where it would serve as a stand-in for her gaze. Instead, she seeks a tactile proximity, where the camera is like a hand or an extension of the skin, or she films her subjects from below, as if to embody a range of erotic, almost genital, urges.

This view—or viewing—from below, accentuated by her use of screens that hang from the ceiling, is typical of many recent works by Pipilotti, such as 4th Floor to Mildness or, perhaps the most emblematic, Homo Sapiens Sapiens (2005), which explicitly evokes the Baroque and Rococo tradition of illusionism with its celestial triumphs, acrobatic Assumptions of the Virgin, and apotheoses of saints and sovereigns appearing to break through the ceilings of churches and palaces. In Homo Sapiens Sapiens, the engagement with Christian iconography is both obvious and provocative, in its consequences if not in its intent. When the work was first presented in the church of San Stae during the 2005 Venice Biennale, the exhibition was closed down after a few months by the Curia—although this episode of censorship says less about the explicit nature of the content than about the Catholic Church’s enduring preoccupation with the power of images and a desire to control the discourse surrounding them. The fact that this work aroused the ire of the ecclesiastic patriarchy shows the still subversive charge of Rist’s imagery, which transforms the passive depiction of women found in traditional Christian iconography into a paean of newly empowered femininity. At the same time, Rist’s digital frescos are directly tied to the history of the Baroque as the style through which the Church sought to captivate its flock during the Counter Reformation, deploying spectacular, illusionistic imagery, precious materials and bold colors, and sensual and emotional tactics tailored to the new mass audiences of the 17th century. With her electronic Baroque, Rist too seeks to envelop her viewers in a hallucinated synesthesia of images, to create a Cathodic Church of Our Digital Lady.

Throughout her work Rist envisions cinema and the projected image as unique spheres that offer an experience of both deepest solitude and shared commonality. Over the years, as an artist and as a viewer, Rist has carefully observed a transformative shift in how moving images are watched and perceived in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. As a child of the 1960s, Rist witnessed the adventure of cinema in all its panoramic splendor, and even glimpsed the hypnotic experiments of expanded cinema (Rist’s first forays into the art of the moving image were rudimentary light and sound installations for concerts). In the 1980s, Rist saw the birth of the music video, and in the 1990s, the spread of the VCR and cable TV. These formative experiences fueled many of her early single-channel videos, which were often presented in the installation The Room (1994), an oversized environment which alludes to the merger between the public space of television and the private dimension of the home. In the first decades of this century, Rist has seen moving images become both more fleeting and more pervasive as they swarm across computer screens and mobile phones—omnipresent, yet tinier and tinier, and often poorer in resolution. “The experience of the moving image has progressively migrated from a communal consumption on big screens to an individual, lonely consumption on smaller screens,” Rist explains. This observation is at the heart of many of her installations, where the artist tries to recreate a shared space where visitors can experience moving images together. In these spaces, Rist pursues what she calls the “melting of knowledge and feelings,” and a “gathering where single humans are joined in a communion.” While Rist’s vocabulary could at first reveal an affinity with the varied stylistic constellation that has come to be known as “relational aesthetics”—and indeed, many artists of Rist’s generation share some of her preoccupations with the understanding and the deconstruction of the machinery of the spectacle—it also places Rist’s practice in a continuum rooted in the techno-utopianism of the 1960s counterculture, which gains a new urgency in our technocratic present.

Rist often wears a blue jumpsuit, proudly explaining it to be an electrician’s uniform she bought in Japan. With this look straight out of Super Mario Bros., she presents herself as a lineworker of perception: an electrician of the unconscious, wiring together flesh and pixels to form a new digital sublime.

A self-proclaimed hippy, Pipilotti Rist is not afraid to imagine art as a form of healing. That’s what she expects of it, she says: “to be consoling and bring some kind of enlarged logic to the way we are.” She believes that machines are always connected to our bodies and identity, so we must merge with them, treat them like the echo of another person. “We are surrounded by so many humming sounds, cables and things going zzzzz: electronic devices and air conditioning and cars, and all this stuff which apparently makes too little sense and too much noise,” she says in her characteristically prophetic, stream-of-consciousness way. “Like in a homeopathic remedy, for you to heal, you need the same thing that makes you crazy. That’s what I am trying to do.”

PIPILOTTI RIST: DESIRING MACHINES

Text by Massimiliano Gioni

CURA.32

THE OCTOBER ISSUE

CREDITS

All images © Pipilotti Rist

Courtesy: the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

PIPILOTTI RIST (b. 1962, Grabs, Switzerland) is a pioneer of spatial video art and has been a central figure within the international art scene since the mid-1980s. Her artistic work has co-developed with technical advancements and in playful exploration of its new possibilities to propose footage resembling a collective brain.

MASSIMILIANO GIONI (b. 1973) is an Italian curator and contemporary art critic based in New York City. He is the Artistic Director of the New Museum in New York and the Director of the Nicola Trussardi Foundation in Milan. Gioni was the Director of the 55th Venice Biennale. He has organized numerous international exhibitions and was co-curator of the Venice Biennale (2003) (curating the La Zona section); co-curator of the 4th Berlin Biennale (2006); co-curator of Manifesta 5 (2004); curator of the 8th Gwangjiu Biennale (2010). In 2002, he opened The Wrong Gallery, in Chelsea, NY, with Ali Subotnick and Maurizio Cattelan. He was US editor of Flash Art magazine from 2000 to 2003.