Text by Emma Enderby

CURA.36 SS2021

FUTURITY

“It turns out that learning how to see the world around us is pretty hard to do,”1 said Trevor Paglen in a 2018 interview. Yet that is just what the artist is dedicated to: the pursuit of seeing. In his investigative work Paglen scrutinizes the invisible practice of power that pervades our lives and manifests in security, warfare, and infrastructural and computational control—surveillance and dataveillance. Digital technologies have transformed public space, intertwined the physical and virtual, allowing structures of control to not only grow in the darkness, but by virtue of their design, to be stealth, unchecked and unregulated. Paglen coined the term “experimental geography” in relation to his work, signaling a background—he obtained a PhD in Geography from the University of California, Berkeley after obtaining his MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—that has aided his visual articulation and self-reflexive examination of space. Works such as Terminal Air (2007) uncover human activity in defining the Earth’s land and sky. The work visualizes extraordinary rendition, a CIA practice in which suspected terrorists detained in Western countries are transported to so-called ‘black sites’ for interrogation and torture. The installation includes a map of real-time movement of these flights, and, as curator Lauren Cornell notes in the above mentioned interview, “a picture of the sky as I’d never seen it.”2

CLOUD #902 Scale Invariant Feature Transform; Watershed, 2020

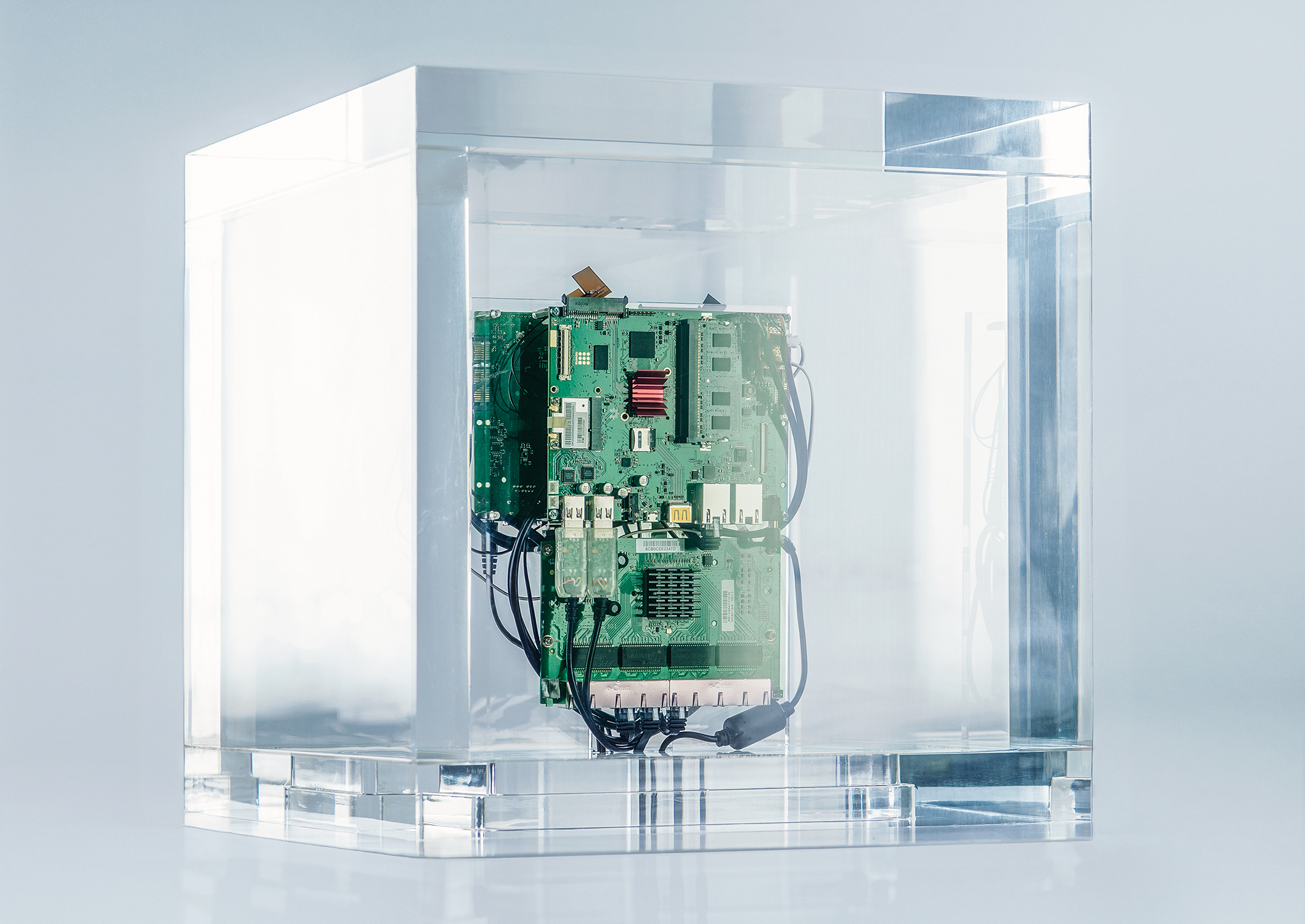

Paglen’s practice is research driven: he often spends years on understanding his subject matter before realizing artworks that frequently appear as series given his investigations are rarely limited to a single output, object or image. His highly collaborative process that has involved computer scientists, software developers, hackers and astronomers is visualized through many forms from documentary film to sculpture where the medium really is the message. Paglen’s ambitious public art projects include a radioactive public sculpture, Trinity Cube (2015), installed in the exclusion zone in Fukushima, and the launch of two artworks into space: the non-functional satellite Orbital Reflector (2016, unfortunately lost to space in 2019), which joined the space junk that circles our world; and, playing off the 1977 Voyager message, The Last Pictures (2012), a silicon disk with 100 images of war and crashing waves among other relics of humanity that will continue to orbit the Earth long after humanity has disappeared. Paglen has also published numerous artists’ books, contributed research and cinematography to the documentary film Citizenfour (2014) and his minimalist sculpture The Autonomy Cube (2015) installed in various museums serves as a wi-fi hotspot on the Tor network that allows for users’ trackless digital movements.

Within this tremendously diverse output, one medium, the photograph, remains a persistent tool and metaphor in the artist’s examination of (in)visible powers—that which is out of sight or hard or impossible to see—that determine our lives. In some photographs, invisibility is gained through the banal, such as in his series An Everyday Landscape (2012-13) and Landing Points (2014-): the former details architecture—anonymous parking lots, generic suburban housing, insurances companies—that all connect to CIA front companies involved in extraordinary rendition; for the latter, he learned underwater photography and scuba diving to capture the vast web of cables that sit at the bottom of the ocean and make the World Wide Web possible while at the same time being routinely tapped by surveillance agencies. In Limit Telephotography (2006), images of classified military sites for the most part situated in the southwestern US and captured using telescopic equipment are unseen worlds on restricted land, away from the public gaze. Their hazy or distorted appearance results from atmospheric conditions and the practice the artist refers to as photographing the limits of his vision, effectively translating the sites’ uncertainty. Yet Paglen’s tendency to use highly descriptive titles to locate the sites jar with both the visible ordinariness of some of the images that include things like airplanes or corporate buildings, and the less visible abstractions, which come across as beautiful or strange. This double vision plays on how true seeing is complicated and has limits.

Bloom (#7f595e), 2020

Bloom (#7b5e54), 2020

Bloom (#7d5c52), 2020

Bloom (#a8866d), 2020

Abstraction, and its art-historical connotations, is used in discussions of Paglen’s work. The artist’s own awareness of the push and pull between abstraction and figuration, serenity and chaos is clear in his various series. His seascapes, works like NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Miami Beach, United States (2015), continue the themes of Landing Points with tranquil beaches and ocean horizons that waver between the sublime and banal. His series The Other Night Sky (2007-) comprises photographs of over two hundred classified satellites orbiting the Earth. The satellites are near invisible to the naked eye. Working with amateur astronomers, Paglen was able to track and catalogue the satellites, timing the exact moment of capture using telescopes and large-format cameras. While the artist exposes the ever-observing ‘eyes’—turning watcher into watched—the outcome of this nefarious reality is a serene collection of beautiful photographs of the night sky that again teeter on the abstract.

Paglen continues a tradition that stems from J.M.W. Turner and was carried on by Agnes Martin and Hiroshi Sugimoto: picturing a landscape through abstraction. He deliberately uses abstraction’s hallmark line, space and color to capture the vastness and intangibility of landscapes, extending this intangibility to the systems of control hiding (and therefore abstracted) within these landscapes. Works like Color Study (Pelican Bay State Prison, Crescent City, CA) (2015) are in direct dialogue with color-field painting, purposefully shot at times of day that create the desired color and tones such that form quietly tackles his subject: state security is entangled with perception; border control or surveillance is visualized by considering their abstracted reality and embedded uncertainty and slipperiness.

There is a paradox, or playfulness, in Paglen’s choice of photography, with its embroiled relationship to (in)visibility, as his main tool in a project oriented around exposure. The medium has always been unreliable due to the subjective impact of the photographer or the doctoring of images. Now that anyone can alter and share an image with a seemingly limitless audience in minutes, the discussion has gained traction. Images, real or fake, change memory and behavior, and artificial intelligence (AI) is the new agent of change. Due to this “fundamental societal shift whose implications we have yet to fully fathom,”3 Paglen has recently been creating a series of works on AI and how machines see us. AI has become the omnipresent tool in which all forms of tracking—from mobile phones to supermarket checkouts—capture, categorize and synthesize information using vision technologies. Its invisibility is distinct from military sites, satellites, corporate American buildings and underwater cables given that machine-sight or machine-images are actually invisible to our eyes. As Paglen notes: “These images aren’t meant for us.”4

It Began as a Military Experiment (2017) consists of ten photographs of military employees from a database of thousands taken in the 1990s that were used to develop facial recognition technology. The algorithm compared physical features, learning how to ‘see’ and therefore identify individuals. Paglen explores this emergent reality in which we are no longer in charge of image making and production. In another series, Adversarially Evolved Hallucinations (2017), the artist used training sets—large volumes of images that train AIs to ‘see’ things—to teach the AI to recognize images associated with taxonomies such as omens, monsters and dreams. The AI then generated their own ‘visions’ of these groupings to surreal, beautiful and chilling effect.

Machine Readable Hito, 2017

The use of photography to explore AI, an invisible power that cannot be decoupled from that medium, is uncannily appropriate as our role in creating photography remains in question. From the time of the ‘fathers of photography’ Louis Daguerre, Henry Fox Talbot and others, the lack of human agency in photography has been questioned by photographers and viewers alike. Jonathan Crary has observed that flight simulators, robotic image recognition and multispectral sensors are “only a few of the techniques that are relocating vision to a plane severed from a human observer.”5 With AI, image production becomes dominated, as Paglen states, “by machines for other machines, with humans rarely in the loop.”6

Like photography, any notion that AI provides a truthful mirror or an objective record is a myth. The biases built into its foundations are endless and its entry into our lives is not democratic. When Michel Foucault questioned the selection, form and appearance of the archive, he taught us that there has never been a persistently objective view in the collection and presentation of knowledge. And as Donna Haraway has famously stated: “Technology is not neutral. We’re inside of what we make, and it’s inside of us.”7

In the Eigenface (2016-) portraits and Machine-Readable Hito (2017), Paglen explores the judgements that are built into technical systems. In the first case, this centers on the notion of ‘face-prints’, the data that makes features mathematically distinct from other faces, which Paglen used to create portraits (such as Franz Fanon and Winona Ryder), revealing the assumptions and conclusions made by defective image data; in the second, he processed hundreds of images of artist Hito Steyerl through various facial recognition algorithms and included their output on gender, age, emotional state, etc., below the images. Machine-Readable Hito built on Sight Machine organized by Paglen in 2017. In this live performance by the Kronos Quartet, cameras attached to computer vision algorithms used in autonomous vision systems such as guided missiles, self-driving cars and spy satellites, project what they ‘see’—like gender and mood—in the audience on a screen behind the musicians. His temporary website ImageNet Roulette (2019) allowed people to upload selfies and find out how the computer classified them—how facial features were seen by AI—ranging from being tagged ‘sister’ to ‘rape suspect’. These works exposed the human biases embedded in the original classification process of ‘ImageNet’, the multi-million-image-strong training set compiled of images taken from the Internet, sorted and tagged by Amazon’s online labor platform.

In two recent bodies of work, Paglen returned to exploring art historical archetypes: clouds and flowers. His exhibition, Bloom (2020), which took place in a year of immense death and loss due to Covid-19, makes the flower a fitting historical motif. His clouds and flowers feel so real yet are generated by an AI taught to create according to their own vision. Clouds and flowers mark our humanity and through their use, Paglen reminds us technology is not ‘other’ but now embedded in our lives.

Autonomy Cube, 2015

While at first glance an exhibition of images of flowers or clouds could seem innocent, innocuous, even cliché—this is the very intention, to put on display the way in which AI enters our lives. The imagined Hollywood sci-fi worlds in which expert systems embedded within humanity are chaotic, blatant and exposed has not come to pass. AI hides in plain sight, in ease: it unlocks our phones with our faces, suggests our friends, gets us from A to B, spell checks our work. Machine learning quietly disappears into the aesthetics and friendliness of our digital experience—it empowers us to input, store, handle, transmit and interpret. But as Lisa Gitelman and Virginia Jackson have noted, “less obvious are the ways in which the final term in this sequence [of data gathering]—interpretation—haunts its predecessors.”8

In Paglen’s night skies, clouds, seas and flowers there is a quiet urgency; stillness is a façade. He pushes for art to expose and critique the instruments that oversee us, that produce our reality. In presenting us with the changing nature of vision, he expands what can be seen and comprehended. “I want art to help us see the historical moment that we find ourselves in,” says Paglen. “I am not interested in ‘timeless truths’ (I don’t think they exist).”9

To quote another artist who reconstructs reality, Martha Rosler: “The future always flies in under the radar.”10 At a moment when technology is quickening past humanity, Paglen contemplates this future and the need to expose certainties so that we might gauge that new reality and ask if it could be different.

1

Trevor Paglen quoted in “Lauren Cornell in conversation with Trevor Paglen,” in Michele Robecchi (ed.), Trevor Paglen (London: Phaidon, 2018), p. 13.

2

Ibid., p. 9.

3

Ibid., p. 33.

4

Trevor Paglen in Jörg Heiser (ed.), “Safety in Numbers?,” Frieze, no. 161, March 2014.

5

Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer (Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press, 1992), p. 1.

6

Trevor Paglen in Trevor Paglen, p. 33.

7

Cited in Hari Kunzru, “You Are Cyborg,” Wired Magazine, February 1997, p. 209.

8

Lisa Gitelman and Virginia Jackson, “Introduction,” in ‘Raw Data’ Is an Oxymoron (Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press, 2013), p. 3.

9

Trevor Paglen, p. 12.

10

See Hans Ulrich Obrist & M/M, The Future Will Be… (Paris: onestar press, 2007).

CURA.36

Spring Summer 2021

THE FUTURITY ISSUE

CREDITS:

All images Courtesy: the artist and the galleries

TREVOR PAGLEN (b. 1974, Camp Springs, Maryland, USA) is known for investigating the invisible through the visible, with a wide-reaching approach that spans image-making, sculpture, investigative journalism, writing, engineering, and numerous other disciplines. Among his chief concerns are learning how to see the historical moment we live in and developing the means to imagine alternative futures.

EMMA ENDERBY is the Chief Curator at The Shed, New York, where she is organizing upcoming shows with Ian Cheng and Tomás Saraceno, and curated the retrospective exhibition of Agnes Denes, along with shows with Trisha Donnelly, Tony Cokes, Oscar Murillo and the institution’s emerging art program Open Call. She previously was a curator at the Public Art Fund, NY and Serpentine Galleries, London.